By Johna Till Johnson

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

There are no extraordinary men, just extraordinary circumstances that ordinary men are forced to deal with.

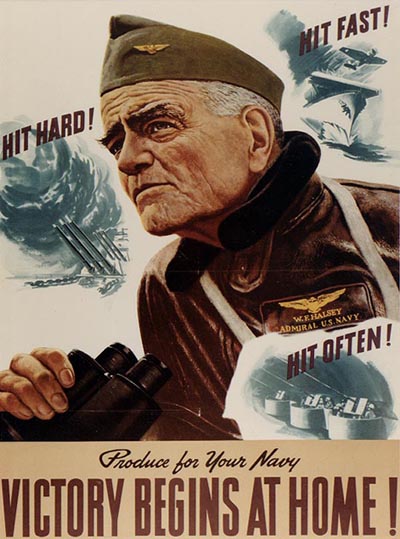

—Admiral William (“Bull”) Frederick Halsey, Jr.

This sketch is one of several inspired by the book, The Admirals: The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea, by Walter R. Borneman. It’s about Admirals Halsey, Nimitz, King, and Leahy, each of whom played critical roles in World War II, and were the only admirals to earn five stars in all of American history. (For the other sketches in the series, see Triptych: Three Admirals.)

More than that, the book is about leadership, character, and how a flawed individual can rise to greatness—not in spite of, but often even precisely because of, those flaws.

Halsey was a pugnacious fighter, wisecracking and hotheaded, whose passion was winning the game (or battle). His courage and determination helped re-energize and inspire a Navy demoralized and depleted by the hideous surprise of Pearl Harbor. Yet his appetite for the fight paradoxically cost him participation in some of the defining battles of the Pacific, and could have cost the war. But anything he did, he did wholeheartedly—and there was never any question of stopping him.

Long before he became Fleet Admiral, William Halsey was known as a fighter. He was a Naval Academy football player, a fullback. And although he wasn’t particularly good—he joked that he was the “worst fullback in the history of Naval Academy football”—he was spectacularly determined. Courage and determination were hallmarks of his character—and the attitude he epitomized was critical to the American Navy’s success in World War II.

But Halsey had more than just attitude. He had vision and the willingness to put himself physically on the line in support of what he believed—even at the risk of potentially embarrassing failure.

He realized early on that aircraft, and aircraft carriers, would be critical to the Navy’s future. In 1933, when then-Rear Admiral King, who was head of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics, offered him command of the aircraft carrier Saratoga if he would learn to fly, Halsey took him up on it—at the age of 52, competing with men half his age. (King had done virtually the same thing himself a few years before.) That’s the kind of man he was—no half-measures.

Halsey’s pilot’s training stood him in good stead eight years later, shortly after the Japanese devastated the American Pacific fleet in the Pearl Harbor attack. Just prior to the attack, Halsey was Commander of Carrier Division 2 in the Pacific. Fortunately, he’d been ordered to take his carrier, the Enterprise, to sea and was delayed from returning by a storm—thus missing the destruction. (Halsey’s relationship with storms remained problematic, and not all encounters were so fortunate.) Immediately after the attack, Halsey was given command of “all the ships at sea.”

And while the rest of the Navy licked its wounds and began painfully to rebuild, Halsey went on the offense. Even though the American Pacific fleet was severely wounded, Halsey attacked the Japanese at the Gilbert and Marshall Islands and Wake Island.

Most famously, his task force supported the Doolittle Raid, during which 16 B-25s, with a total of 80 men, launched from the aircraft carrier Hornet and bombed Tokyo and a handful of other Japanese cities. The airmen were out of fuel for the return trip, so they crash-landed in China and Russia. Amazingly, 69 of the 80 escaped and survived. It was an astonishing feat of courage—made possible in part because of Admiral Halsey’s deep understanding of the potential of naval air forces.

Although the raid did little actual military damage, it served as a tremendous morale boost (coming just four months after Pearl Harbor), and added momentum to Halsey’s growing reputation as an American fighter to watch.

Halsey went on to rise to command of all the South Pacific forces, and make more substantive military contributions in and around Guadalcanal and the bombing of Rabaul in 1943. The latter, in particular, represented a risky, gutsy strategy: an all-out attack against a heavily-fortified naval base, with the goal of damaging as many ships as possible (rather than taking out a few). It was the same tactic the Japanese had deployed at Pearl Harbor—but this time it was used against them.

The risky attack succeeded spectacularly: six out of seven Japanese cruisers were damaged, and the Japanese were forced to retreat. That raid, along with the launch of the first wave of American warships built over the previous two years, served to swing the advantage in the Pacific to the Americans, where it remained until the end of the war.

But Halsey was defined as much by his failures as his successes—both of which stemmed from his relentless eagerness to engage. During the momentous battle of Leyte Gulf in 1944 (which resulted in the collapse of the Japanese Navy and ultimately led to the liberation of the Philippines) Halsey missed virtually all the fighting, and made a critical mistake that almost cost the battle.

The Japanese were launching a two-pronged attack from the west and south of the Philippine Islands. In addition, the Japanese Northern Force was deployed as a third prong, serving a decoy. Comprised of two aircraft carriers, some decrepit planes, and a few supporting vessels, the Northern Force’s goal was to draw American firepower away from the battle.

The Japanese plan worked beautifully. Halsey took the bait, and raced his powerful Third Fleet north, convinced he was hot on the trail of a major strike force. Worse, thanks to a communication mixup, he left the San Bernardino Strait—through which the Japanese Center force planned its western assault—almost entirely unguarded.

Halsey had created Task Force 34, a contingency strike force for protecting San Bernardino Strait. But he hadn’t deployed it because he mistakenly believed the Japanese Center Force had already been routed by American forces.

Unfortunately, the exact opposite was true: the Japanese warships, hardly believing their luck, were pouring through the strait into the American fleet’s virtually undefended middle. (The rest of the American forces were already heavily occupied defending the south against the attacking Japanese South Force).

Heroic action by outgunned American vessels (most of which were lost) was the only thing that kept the Japanese Center Force at bay. (Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague’s order sending the fleet of destroyers and escort vessels against the Japanese Center Force was, fittingly, “Small boys attack.”)

Meanwhile, Halsey and his powerful carriers were miles away from the real action, chasing the Japanese decoy. The rest of the American fleet sent increasingly desperate requests for backup, which Halsey either ignored or did not receive. Finally, Admiral Nimitz, back at headquarters, sent an urgent telegram asking for Halsey’s whereabouts: “Where is, repeat, where is Task Force Thirty Four? The world wonders.”

The last three words, “The world wonders,” were actually intended as padding words, nonsense words to indicate the end of the message (the cryptographic equivalent of “stop”). But Halsey read them as an indictment of his strategy—with the implication that Halsey was deliberately staying away from battle.

Sources vary regarding what happened next. Some say Halsey began to cry in frustration—over missing the battle, and worse, having his boss believe he was deliberately shirking a fight. Others say—perhaps more diplomatically—that he began to swear.

Regardless, it’s an indelible image: a 60-something, multiply decorated Admiral having an emotional meltdown because his courage was questioned.

In any event, after Halsey’s outburst, he turned the fleet around and steamed back towards San Bernardino Strait. He arrived too late to make much of a difference. But by then, the Japanese had, amazingly, decided to retreat back through the strait.

Why? As the Japanese later acknowledged, the Center Force retreated because it believed, mistakenly, that it was facing Halsey’s full fury. According to Evan Thomas’ book Sea of Thunder: “(Center Force Admiral) Kurita remained convinced that he had been engaging elements of (Halsey’s) 3rd Fleet, and it would only be a matter of time before Halsey surrounded and annihilated him.” That’s probably accurate—having missed the fight once before, it’s likely that Halsey would have behaved exactly as Admiral Kurita predicted.

Thus, the Battle of Leyte Gulf represented a stunning victory for the Americans. And it’s fair to say that Halsey’s fearlessness and reputation had an outsized impact on the outcome, even in the absence of himself and his fleet.

Halsey’s unwillingness to back down got him into further trouble later on, when he managed to lead his fleet not once but twice—on two separate occasions—right into the path of an oncoming typhoon. The first time he lost several ships, and the second instance resulted in a letter of reprimand—normally a career-ending measure. But in light of Halsey’s tremendous performance otherwise, it was not—Admiral Halsey went on to earn a fifth star.

Thus, Halsey’s Third Fleet was present at the very end of the war, preparing for an all-out assault on Japan (which never happened). Even after the Japanese surrender, Halsey remained wary and famously advised his fleet: “War is over. If any Japanese airplanes appear, shoot them down in a friendly way.”

The Japanese formally surrendered on the deck of his flagship, the Missouri, on September 2, 1945. Halsey was present.

In 1957, the US Naval Academy named the Halsey Field House after Admiral Halsey. I like to think that the former Naval Academy football player was pleased by the honor.

Pingback: Triptych: Three Admirals | Wind Against Current

Reblogged this on Locating Frankenstein's Brain.

LikeLike

Thanks for reposting!

LikeLike

Pingback: Halsey: The Unstoppable - ONews.US - Latest Breaking News | ONews.US - Latest Breaking News

Wünsche einen schönen Dienstagabend <3

LikeLike

Thank you! It WAS a lovely evening, in fact.

LikeLike

A great read, Johna. Love Halsey’s last command. :)

LikeLike

Me too. It gives you a sense of his humorousness and wittiness.

LikeLike

Riveting reading. It is amazing to think that he was probably a decisive factor in winning a battle even though he had made a tactical error and had missed the action!

LikeLike

Yes, interestingly, years later one of the other admirals noted that he blamed Halsey–but not for the battle, for the typhoons. (I glossed over that, but he made a major tactical mistake in underestimating the strength and path of a typhoon.. then did it AGAIN. Listening to reports was clearly not his forte!)

At any rate, he was a fantastic warrior and decisive factor in winning the war… despite mistakes.

LikeLike

I guess it shows that few celebrated hero’s are immune to errors – mistakes. In reference to Leyte Gulf, one mistake seemed to be neutralized by another, ….the stakes are so awfully high!

LikeLike

Yes, that’s what amazes me: You (well, I) think of these guys as larger than life–but as Halsey himself says, “There are no extraordinary men…”

And one thing that leaps out at me is that the mistakes are inseparable from the successes. Halsey’s emphasis on striking hard, fast, and with all one’s might was what helped him succeed, but also got him into trouble.

Thanks again for reading, and posting!

LikeLike

Riveting! What a great read! Thank you!

LikeLike

You’re welcome! And thanks for reading, and posting!

LikeLike

Men.

LikeLike

And women :-)

LikeLike

Excellent post, Johna! Thank you :)

LikeLike

You’re welcome! More to come….

LikeLike

Fascinating information here.

Can I admit I know next to nothing about WWII?

Don;t laugh but I went to Catholic grammar school and the nuns NEVER got far enough in the history book, We learned about the Greeks and Romans, he Crusaders and Inquisition and that was it!

WWII didn’t get covered in my Catholic High School either where History classes focused on ancient/biblical history and/or current events.

I’ve always wondered if I just went to two shitty schools or if this was the norm in Catholic ed during 1960-75 Anyone know?

LikeLike

You aren’t alone. Strange but true factoid: In the 1970s, my parents were visiting family friends in Europe who had lived through the war as children/teens. These were highly educated professionals: A doctor and a novelist of considerable fame.

Neither one had ever heard of Pearl Harbor.

They literally didn’t know why the US entered the war, or that we’d been attacked. Because, well, they’d been living in bombed-out houses under German occupation at the time. And afterwards, there was plenty else to focus on.

At any rate, recent history is often very hard to teach, because the narrative isn’t fully settled at the time, which makes it hard to create the “textbook version” to go into textbooks.

I never learned much modern history (and yes, I went to Catholic schools, in different countries) but I think it has more to do with the challenge of teaching events that fall “in the gap” between history and current events than it does to the schools being either Catholic or particularly bad. (For instance, I think it’s way too soon to teach the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, in part because we truly don’t know the outcome yet. But these wars are already over a decade old…which means there are young adults out there who have only a vague understanding, if any, of what led up to the US launching these wars.)

Okay, enough rambling! Don’t know if I answered your questions, but thanks for reading, and posting!

LikeLike

I learned a lot! Thanks Johna : )

LikeLike

Johna is working on the next one… :-)

LikeLike

YAY!

LikeLike