By Johna Till Johnson

(Additional material contributed by Vladimir Brezina)

Yesterday, I wrote about the Bayonne Bridge’s 80th birthday. The Bayonne Bridge is one of the loveliest—possibly even the loveliest—bridge in New York Harbor.

Yesterday, I wrote about the Bayonne Bridge’s 80th birthday. The Bayonne Bridge is one of the loveliest—possibly even the loveliest—bridge in New York Harbor.

But I neglected to mention something in that post. Not because I’d forgotten, but because I don’t like to think about it: Current plans are for the Bayonne Bridge to undergo a structural makeover.

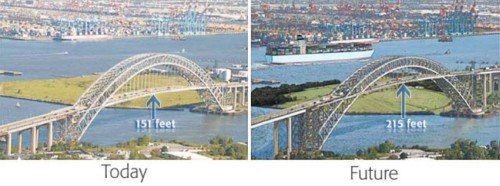

The roadbed of the bridge is being raised from 151 feet at high tide to 215 feet to accommodate the new generation of post-Panamax container ships.

Why is this happening? As the graphic shows, container ships are growing to huge proportions—much larger than was even remotely foreseen in 1931 when the Bayonne Bridge opened. But until now, the size of these ships has been limited by their need to fit through the Panama Canal. This “Panamax” generation of ships still fits under the Bayonne Bridge (although barely, as Tugster has documented here and here and here).

But now the Panama Canal is being widened. When the widening is completed—very soon, in 2014—a new generation of post-Panamax ships will roam the world. These larger ships will go wherever ports can accommodate them. And right now, because these ships can’t fit under the Bayonne Bridge, this won’t include New York’s main container terminals in Port Newark / Elizabeth.

(To accommodate these huge ships under the water, the Kill van Kull also has to be dredged, but this work, although expensive, is relatively straightforward, and is already well advanced. )

The makeover of the Bayonne Bridge is therefore absolutely essential to the economic health of the New York-area shipping industry. As a New Yorker, I support it—I don’t want to see New York degenerate into a picturesque relic of times gone by, which is what happens when conservation trumps innovation.

And I cherish the nothing-is-sacred mentality of New York authorities when it comes to staying alive and competitive.

Nonetheless, the change breaks my heart. Because although the graceful steel arch will remain unchanged, the proportions of the new Bayonne Bridge will be all wrong. Instead of a graceful parabola arcing majestically through the roadbed, the new bridge will be a tiny crescent slice sitting high above the water. (Notice the cleverly photoshopped container ship in the background of the “Future” picture!)

Although the redesign is functionally and economically necessary (and fascinating from an engineering perspective), the end result will lack Gustav Lindenthal‘s “pursuit for perfection and his love of art.”

Alternative solutions were considered: A tunnel under the Kill van Kull, or even a completely new bridge next to the Bayonne Bridge, which would have had its roadbed removed, leaving just the steel arch “in a nod to local and architectural history”. But these other options have now been rejected as more expensive and time-consuming.

Even the planned makeover of the Bayonne Bridge will cost at least $1.32 billion and take at least nine years to complete. With the dickering of local politicians, though, the start date has not even been set, while the post-Panamax date of 2014 looms…

So if you want to see the Bayonne Bridge in all her perfect glory, as her creators intended—you still have some time. But go soon.

How very interesting – just raise the road bed. Seems easy enough, at least on paper. As one who generally favors multiplicity, redundancy and variety, I have to question if the larger, post Panamax ships are really more effective for transportation of goods.

LikeLike

“Multiplicity, redundancy, and variety”—certainly! Container (and other) ships will presumably always be needed in a range of sizes, from small ones for short sea shipping to the largest ones that go around the world.

But for the large ones, the trend toward increasing size is clear. It hasn’t really been interrupted by the recent bad economy—companies are still betting on ever-larger ships for the future.

Why? The basic answer is pretty much what you might expect: economies of scale. Taking into account just the cost to the owner and operator of the ship (and yes, ignoring other factors such as environmental impact), it’s just cheaper per container to build and operate a larger ship. Once you are going to build a ship of a certain size and pay for fuel and crew, the marginal cost of making the ship just that much larger still to accommodate additional containers goes way down. According to this interesting review of the various factors involved published by the classification society Det Norske Veritas,

“Two decades ago, studies were published comparing two 4,000 TEU ships to one 8,000 TEU ship and showed a reduced total cost per unit. Today, a comparison between two 8k TEU ships and one 16k TEU shows the same trend. The capital cost for the bigger ship is in the order of 20% less and the fuel cost around 40% less…”

But there are limits. Especially for the largest ships, many technical and economic factors trade off against each other—issues of structural integrity and engine power, and how well will the ship work with existing port facilities? There may in fact be a “sweet spot”, below the maximal size possible (which in the foreseeable future might be 22k TEU), at which the increasing size of container ships will settle (as has already happened with oil tankers). The author of the Det Norske Veritas study believes so:

“If I were to make a prediction about the size of the typical big container ship in the future, I would tend to say that the NPX (about 12.5k TEU) that will go through the new Panama Canal (366m x 49m) and under the Bayonne bridge is likely to be the predominant size. It combines economy of scale with flexibility and versatility, and that is likely to make it a winner.”

But that would be the new Bayonne Bridge, after the roadway elevation…

LikeLike

I too have to question the unquestioning acceptance of the shipping industry claim that huge ships are vital to the continued economic health of our region. With the bridge-raising and the dredging that preceded and will no doubt follow it, we’re getting whipsawed into spending billions in public money with virtually no public discussion or review. How exactly will these ships and the box stores they feed improve our lives or create real jobs? What are the impacts on the estuary? Is this really an ‘innovation’ or is it a giant giveaway?

LikeLike

Hi Rob,

You ask a great question. I’m in no way favoring blind acceptance of the claims from powers that be that such-and-such will result in “job creation”. (Ha!).

And it’s also true that the shipping industry is so automated these days that it takes a handful of people to do what it once took thousands. So we can’t be talking about a truly huge number of jobs.

That said, though, every container that comes in has to be unloaded, dropped onto a truck, and transported to its destination–and someone has to do all that (not to mention operate the rest stops for truck drivers, etc.). Then there are the tugboat crews and the ship pilots, and the infrastructure that supports them.

So I think it’s fair to say that modifying the bridge to support bigger ships will definitely create jobs. How many? Hard to say. Enough to justify the investment? Probably–if only because enhanced infrastructure almost always justifies the investment, unless it’s done blindly without a clear need (not the case here–there is an existing port).

I guess my general sense is that New York is among a small handful of global cities that is not only rich in history and natural resources, but actually a vibrant and functioning commercial city, supporting a range of industries (including shipping). I used to live in Europe, and one thing that’s depressing there is how many cities feel as though time has passed them by. They’re quaint, but fundamentally obsolete.

What attracts me to this city (the only place I’ve ever chosen to live) is that feeling of being the “center of everything”–a place where real stuff happens.

I’d hate to see us lose that.

LikeLike

There are still other options, of course. One obvious one is to move the container port, or at least the part of it that will handle the largest ships, to a different site where it will no longer be obstructed by the Bayonne Bridge—for example, to Bayonne’s old Military Ocean Terminal. There are some signs that the Port Authority is considering moving in that direction. But it’s very true that the maneuvering behind the scenes for and against the various options is very hard for the public to penetrate.

LikeLike

just fyi–and because it seems like you two would be interested and because i think the more discussion/debate about this, the better–i wrote a letter about the lack of public process here. it’s in the latest waterwire, the mwa newsletter, but will try to paste it below too. rob

Put the Bridge on Hold

To the editor,

I’m wondering how many otherWaterWire readers saw the August 20 article in the New York Times entitled “Panama Canal’s Growth Prompts U.S. Ports to Expand.” Despite the innocuous headline, it made the startling suggestion that some key people inside or connected to the shipping industry have doubts about the wisdom of our current rush to pursue a number of ambitious, hyper-expensive port development projects simultaneously. For that reason, I think anyone in interested in the future of our harbor and estuary ought to give it a read.

The new, super-sized Panama Canal is scheduled to open by 2015, and for years now local industry proponents and their allies in the quasi-public “authorities” and “development corporations” that now seem to run the waterfront have been telling us how crucial it is that we be ready for the super-sized container ships that will surely follow. First there was the Harbor Deepening project, which took our main channels to a depth of 50 feet even though in places it meant blasting deep into the bedrock. The cost: at least $2.5 billion. Now there’s the Bayonne Bridge, whose roadway needs to be lifted from 151 to 215 feet in order to accommodate the behemoths’ massive “air draft.” The estimate for that is a paltry $1.3 billion, but doesn’t count related projects like the replacement of the DEP “siphon” that provides water to Staten Island ($250 million). The bridge-raising is a jobs bonanza that can’t happen too soon, we’re told–and indeed, an obliging President Obama ‘fast-tracked’ its environmental review this summer under his “We Can’t Wait” employment initiative.

But do we really need or want to re-engineer our harbor for–let’s face it–the benefit of Walmart? Can we even afford to? One local wrinkle not mentioned in the Times piece is that while the capital funding needed to get the channels down to the requisite depth was secured, there does not seem to have been anything put aside to support maintenance dredging–an annual expense that some say could total $150 million or more.

For environmentalists, recreationalists and others interested in returning the estuary to some semblance of ecological health and productivity, it’s hard not to feel that we are getting bum-rushed here. Over the past decade, hundreds of public servants, scientists, educators, community groups and concerned citizens have dutifully worked with the Army Corps of Engineers, the EPA, and other government agencies to compile something called the Comprehensive Restoration Plan. It’s a blueprint for estuary restoration whose goals, everyone officially agrees, are both worthy and feasible. But with Congress strapped for cash and our prized 50-foot channels already silting in, where is the money likely to go?

It’s possible, of course, that the port industry advocates are right — that we need the superships, and that the glut of foreign-made goods that they will bring and the box stores that they will inevitably spawn is the price our region has to pay to stay competitive and prosper. But how can we know that without getting a close look at the economic arguments for the project, and without commissioning real studies of both the comprehensive environmental impact of harbor development and the economic value — including the generation of new jobs — that could result from alternative approaches? Most importantly, how can we, the public, be expected to accept the proposed developments and expenditures without a full public debate of all the issues?

Fast-tracking isn’t the answer here. We need to resist the pro-development drumbeat, put the bridge-raising on hold, and take the time to have a truly transparent and inclusive discussion about what kind of port and what kind of estuary we really want and need. It’s called planning.

Rob Buchanan

The author is a co-founder of the Village Community Boathouse, the Brooklyn Bridge Park Boathouse and the New York City Water Trail Association, and the New York co-chair of the Citizens Advisory Committee to the EPA’s Harbor & Estuary Program. The views expressed here are his own.

LikeLike

HI Rob,

Thanks for posting this!

As someone who’s done my share of community and environmental activism, I’m all in favor of communities speaking out. There’s pretty much no other way to have our voices heard–and as you point out, “fast-tracking” is all-too-often basically a bum rush designed to get pork-barrel projects rammed through against the wishes of people who are most affected.

That said, I have some reservations about subjecting the Bayonne Bridge redesign to “death by perpetual study committee”. Yes, we should have a comprehensive look at the potential impact of this massive project–but only if we’re actually open to the idea that it might have to happen, and happen quickly, if New York is to maintain a future as an industrial shipping port.

Here’s my issue: If Port Newark can’t accept the supercargo ships, they’ll go elsewhere. This isn’t a hypothetical, or a “maybe”. As Erik Baard pointed out on the nyc-water-trail Google group, they WILL go somewhere else. Now, maybe that’s a good thing–and maybe it’s not.

I have no way of knowing how much irreplaceable estuary environment would be destroyed by this project, but a safe bet is “some”. (When does a development project NEVER destroy the environment?).

I would also wager that the answer to “how much of the New York industrial shipping business would be destroyed if we don’t accommodate the supercargo ships?” is “quite a lot”.

If supercargo ships don’t come here, there goes not only New York’s future as an industrial port, but also the 300,000-plus jobs that the NYC Working Harbor Committee estimates are tied to commercial shipping (their site is http://workingharbor.com/index.html; the stat is from an announcement at the Labor Day tugboat races).

So yes, we can do more studies and try to better quantify things like “some” and “quite a lot”.

But at the end of the day, the choice is pretty stark: We can either continue operating Newark Harbor as a commercial entity, or shut it down.

Personally–and this is just a personal preference–one of the things I like about New York is the mix of natural and industrial beauty. Yes, there are gorgeous natural habitats–but there are also working tugboats and containerships. There is not just an economic but also an esthetic cost to eliminating these. And I simply disagree that Walmart is the only (or even major) beneficiary of New York as a functional commercial shipping harbor.

So yes, openness is a good thing. And as a professional researcher, I’m all in favor of more studies :-) But if the goal is to shut down the project by subjecting it to the delaying tactic of “more studies”–then I can’t agree. I really want New York to continue to have a future as a commercial shipping harbor.

Again, thanks for posting. I can’t agree more that the most productive thing that can happen now is an active debate!

LikeLike

One aspect of this that I didn’t notice in the discussion is the possibility of environmental givebacks or offsets. We might not have enough force to overcome the momentum of this project, but perhaps we could reasonably demand that greater work be done to balance estuary damage with restoration. Keeping things local, some ideas: expansion of the marshy expanses of the Arthur Kill or seeding in new ones on the Kill Van Kull; better care of Shooters Island and its sisters; native plantings along the shores; local CSO mitigation in NJ and on Staten Island, etc.

Erik Baard

LikeLike

I LOVE those ideas, Erik!! As Rob says–open discussion… maybe we can accomplish something here!!

LikeLike

Johna,

Thanks for your response and hope you don’t mind me posting this on the NYC Watertrail list as well as your site–I’d like to keep the conversation going in as many places as possible.

I m not sure what i’m advocating for here is “death by perpetual study.” I think what i’m trying to say is that until now there hasn’t been ANY real study here, either of the supposed economic benefits or the environmental consequences. Nor has there been any meaningful opportunity for public comment or participation. On those grounds alone–lack of due diligence and lack of democracy–I think a time out is justified.

Another aspect of this that makes me uncomfortable is the supposed need for haste. You say we need to be “open to the idea that this might have to happen, and happen quickly”–but why, exactly? If you read the Times piece carefully, it’s not at all certain that significant numbers of superships will start to call here anytime soon. Is it possible that the Port Authority is building a white elephant? It’s happened before. Does anyone remember the Fishport project in Erie Basin? Here’s a link: http://www.nytimes.com/1988/07/27/nyregion/only-the-fish-are-missing-at-fishport-in-brooklyn.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

I also don’t understand the doomsday language. Would a delay of a year or two–or for that matter, ten–really “destroy” the port? Is our choice really between accepting the superships or “shutting down the Port of Newark”? I don’t see how. It’s not as if the harbor and the facilities we have now are going to dry up and blow away, and it’s not as if the market–the 40 million people who live in the region–is going to evaporate. Shippers will still need to get goods to that market, and they’ll still use ships to do it because moving freight by water is always going to be cheaper than moving it by land, regardless of vessel size.

I liked your argument in an earlier post about old European cities that were quaint but obsolete. I don’t want New York to become that either. I think there’s a sustainable vision for this harbor that includes an active working waterfront–in fact, one that’s more active than what we’ve got now. I’d like to see more stuff moving locally by water and less by land, and I’d like to see more of our young people grow up using the waterways and eventually finding employment on them. I’d also like to see an estuary whose fisheries are restored, whose wetlands are robust enough to filter runoff from the land and absorb storm surge from the sea, and whose water is clean enough for swimming everywhere. I don’t see how rushing to transform the KIll van Kull into another Panama, with no real research or public debate, will bring us closer to either goal.

Rob

LikeLike

Hi Rob,

By all means post. As you said up front, the more discussion the better!

I think we agree more than we disagree. I particularly agree with your statement here:

“I don’t want New York to become that either. I think there’s a sustainable vision for this harbor that includes an active working waterfront–in fact, one that’s more active than what we’ve got now. I’d like to see more stuff moving locally by water and less by land, and I’d like to see more of our young people grow up using the waterways and eventually finding employment on them.”

Amen, and that’s a mission statement right there! Sign me up.

I did want to clarify my “doomsday language” and my “death by perpetual study committee” comments, though.

Just to be clear, I’m not insinuating that you or anyone else is proposing “death by perpetual study committee”. That was a reaction (perhaps an overreaction) to what I’ve seen happen in some cases, where instead of opposing an idea directly, someone will recommend “further study” with the goal of delaying the project to keep it from happening at all.

Again, nothing you’ve said implies that this is your point of view! I’m reacting to something you didn’t say, and I shouldn’t have.

As you said above, you’re proposing SOME study rather than NO study–something I wholeheartedly agree with.

However, I do think there’s a real timeline here, and we need to understand what it is. Once the supercargo ships start steaming, activity will move to ports that can accommodate them and away from those that can’t.

It’s like what happened when railroads (or later, interstate highways) were built: Even though the original roads were still there, traffic shifted to the new routes–and didn’t return to the old routes, even if they were later upgraded. That’s because the entire infrastructure shifted to follow the new flows.

There’s a limited window of time between the launch of the first supercargo ship and the point at which the traffic flows become more-or-less permanent–and if we’ve shut ourselves out of the innovation by not acting early, it’s not something we can fix downstream.

I can’t say how long it will take for this to occur (I’m not an expert in transportation technology) but I can say that it WILL occur—there will be an inflection point at which momentum shifts away from the old pathways into the new ones. And if we wait until then to act, it will be too late.

To tie things back to the less theoretical, if we do an extended study and arrive at the conclusion that raising the Bayonne Bridge is, in fact, the optimal solution–it’s pointless if that conclusion is arrived at AFTER the shipping routes (and associated infrastructure) has already shifted.

So I think any call for additional study needs to be both clear on what constitutes “enough” study (whether that’s duration, inclusion of specific groups, or whatever) and some recognition that things are moving quickly and we want to recognize the need for taking whatever action is appropriate within the window of opportunity.

I hope that clarifies my position a little more. And thanks for opening up the dialogue. The more people who discuss and debate this the greater the chance of arriving at an optimal solution all around–not just a solution that benefits some folks.

LikeLike

We’ve been discussing the global forces with which New York City’s maritime industry must contend. But we must also be mindful of how local industries throw elbows at each other. A company in this town needn’t be dying to die — it can be turning a profit, yet still wake to find its lease renewal thrown into doubt by competition from a higher-bidding, even more profitable company from an unrelated industry. This jostling is even more hazardous to waterway dependent industries, for which location is paramount.

As Rob writes, our harbor and facilities will not “dry up and blow away.” No, they’ll be paved over or swallowed by retail or residential developments. Some of our region’s docking facilities, left fallow, have already become parking lots for the kind of big box stores Rob opposes. Condo towers cast shadows across stilled barge slips and gantries, and more are planned. Meanwhile, the wait list for dry docks now stretches into years. These losses are typically irreversible, at least within the span of a few generations.

If Rob wants us to take a deliberative time out, we’ll have to protect those parcels more effectively than we’ve done in the past. But how? We need solid proposals. Despite Melville’s description of the New York wharves as a place where “meditation and water are wedded forever,” don’t count on today’s waterfront vacuums being preserved for thought before action. Even the derelict edges that kayakers, artists, and romantics cherish are often mere spandrels between poorly sited car compounds, self-storage warehouses, and other fully terrestrial (and passive) businesses that supplanted maritime trades.

That said, I’m actually comfortable with some entertainment and residential newcomers to the waterfront, so long as they’re environmentally sustainable and bring inclusive life to the harbor and estuary (we need better partnerships and regulations to achieve those goals).

We could have an even more wonderfully diverse harbor that crackles with urban energy at street ends and also boasts vast stretches of revitalized estuarine habitat restoration areas. Superships could help us get there.

Superships require a smaller real estate footprint ashore than would the aggregate of smaller vessels that would bring goods from deep ports like Norfolk and Halifax via “short sea shipping,” a European term for smaller land-hugging cargo carriers known in the U.S. as the “marine highway” and codified as “Coastwise trade.” Loading and offloading activity has continually condensed throughout our harbor’s history; as ship sizes grew, the number of piers declined even as trade multiplied. Remember that Walt Whitman’s “Mannahatta” was a “city of spires and masts” where virtually every downtown street led to pier. More recently, containerization pulled shipping into massive terminals.

Trucking is an environmental failure and I’m confident that the data will continue to bear out my admitted prejudice. Within NYC’s urban density, habitat and human health are intertwined. Any kid with asthma near a trucking hub like Hunts Point will tell you that, and the World Health Organization quite belatedly recognized in June that diesel exhaust is a carcinogen. Add to that the asphalting of soft earth, increasing habitat fragmentation, the “heat island effect,” and runoffs laden with automotive fluids.

Rob argues that the trucking fear might be a straw man. “[I]t’s not as if the market–the 40 million people who live in the region–is going to evaporate. Shippers will still need to get goods to that market, and they’ll still use ships to do it because moving freight by water is always going to be cheaper than moving it by land, regardless of vessel size,” he writes. But such rhetorical dualism can’t wave away a muddled and damaging reality. It’s not that trucks will replace all shipping, but trucks will replace more shipping if the port languishes in at least partial obsolescence.

So, yes, studies are urgently needed. But I believe those studies should primarily focus on developing a holistic improvement of the harbor with special attention to the Kill Van Kull area. To undertake such a major infrastructure project in seeming isolation from improving other characteristics of the waterway is antiquated thinking.

Study what environmental restorations should be instituted along with infrastructure upgrades. Study how much land might be freed by a centralizing the flow of goods away from smaller vessels and trucks, and how that land should be used. We should demand that officials integrate the fullest possible community input on both fronts. But don’t leave New York Harbor on the shoals of the twentieth century.

Erik

LikeLike

Oh oui, quelle beauté d’envol dans cette arche ! Vraiment une oeuvre magnifique, un appel d’infini ! Quel désastre si l’on touche à cette structure!

Dans l’extrême beauté de cette photo l’on peut voir aussi tout ce qu’apporte la sensibilité d’un regard.

LikeLike

Looks like they are going to do it, and do it soon. But at least then it will a unique bridge, with proportions that no other bridge in the world has… ;-)

LikeLike