By Johna Till Johnson

(With additional text, charts, and photos by Vladimir Brezina)

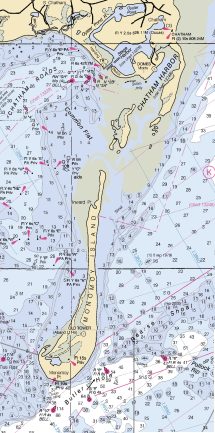

The day dawned clear and bright, and we were excited: This was the day we were going to circumnavigate Monomoy Island. Located at the “elbow” of Cape Cod, Monomoy juts out some eight miles, dividing Nantucket Sound from the Atlantic Ocean. It offers a nice spectrum of paddling opportunities: The protected, shallow water of the Sound on one side, and the deep swells of the Atlantic on the other.

And then there is Monomoy Point, the very end of the island, where the two waters meet.

“Kayakers have died there,” Vlad informed me cheerfully over breakfast.

“Well, they were unprepared,” he added, seeing my look of surprise. “They were trying to round Monomoy Point, didn’t realize how rough the water would be at a point like that, and they capsized.” [See note at end of post.]

I gave him a wary look, eyebrows raised. It’s not like I’ve never been “unprepared”. And what, exactly, did he mean about “how rough the water would be at a point”?

He hurried on, attempting to be reassuring: “It was winter. And I don’t think they drowned. I think they died of hypothermia.”

“Mmmm,” I said, noncommittally. I’ve learned to take it very seriously when Vlad comments, however offhandedly, about the challenge of any particular paddling route. He’s an experienced paddler in a very stable boat, and even routes that he considers “boring” can be rather, ahem, “exciting” for an intermediate paddler in a less-stable boat. And Vlad is constitutionally prone to understatement—he doesn’t like to cause people to worry, or make a fuss. So I wasn’t entirely reassured by his attempts.

But he had a point. It wasn’t winter, it was a beautiful July morning. The rising sun was already filtering through the trees surrounding our campsite, and the weather was predicted to be close to perfect: air temperature in the low eighties, light breeze, mix of sun and cloud. We would be fully prepared, with food, water, and emergency gear—not to mention a full complement of navigation equipment: GPS, compasses, and (so we thought) up-to-date charts.

Moreover, yesterday’s paddle, while memorable, hadn’t been particularly challenging: up the inner coastline of Cape Cod Bay, a break for lunch on top of a sand dune, and back again—all in calm, jade-green water. We’d seen—and swum with—dozens of seals. And we’d enjoyed fantastic vistas of unspoiled nature.

But from a paddling perspective, the trip had been… dare I say it? A bit boring. No conditions. No navigation required: just keep the shore on the right or left side of the boat.

So today we were ready for something that might be just a bit more exciting. True, circumnavigating an island shouldn’t pose any significant navigational challenges. (Famous last words.) And the Nantucket Sound side of the island was likely to be calm and relaxed. However, there was the chance of some real surf on the Atlantic side. Plus, what was that Vlad was saying about “rough water at the point”?

At any rate, we were ready for a trip that would test our mettle. And we weren’t disappointed.

Anticipating a nice picnic on the beach, we packed a lunch of fruit and sandwiches, with plenty of water, and set off.

First challenge: Locating our chosen launch site in Chatham’s Stage Harbor. This turned out to be harder than it sounds. After aimlessly driving around some back streets, we decided to park and launch from a random street that ended on water that we were reasonably sure was part of Stage Harbor.

Next challenge: Finding the way out of the harbor into the open Sound.

Since we didn’t know exactly where we were, we weren’t quite sure in which direction the open water lay. I ended up with the winning guess: A small channel between two sand dunes led us past the Stage Harbor Lighthouse, out into Nantucket Sound.

The northern end of Monomoy lay right in front of us. With a favorable current, tailwind and following seas, we made good time toward the island. That is, at first.

Vlad kept warning about “shoals”—marked in green on our charts—and I realized after a while that I wasn’t entirely clear of the meaning of the word. (I thought “shoals” had something to do with “rocks”, yet none were in sight.)

I soon found out what these “shoals” were, when we encountered them. They’re vast stretches of shallow water, which can become land at low tide.

They were very pretty, with the peekaboo rays of sunshine glittering off the sandy bottom—but not very effective from a paddling perspective. The shallow water slowed us down to a crawl, even with the wind and seas pushing us forward.

So we took a long circuitous route designed to keep us off the shoals—and Vlad seemed quite pleased when the plan worked. We stayed off the shoals, which were precisely where they were supposed to be, according to our charts. I was a bit puzzled by this: Why wouldn’t something be right where it was supposed to be on the chart?

I would find out, but not for a while.

We paddled along past the island, admiring the green water and golden beach. No other humans were in sight. Just a few seal heads popped out of the water, and a host of seabirds swirled overhead.

Because we took the long way round the shoals, and also because the wind was now (as predicted) shifting against us, it took us somewhat longer than we had expected to reach the south end of the island. Finally, its abandoned lighthouse popped into view, and we were almost there. We decided to take a pit stop and assess our options.

We landed on the sandy beach still on the protected Sound side, an easy landing in the gentle, almost nonexistent surf. It was early afternoon. Did we want to have lunch now, or round the point and look for a nice spot to land on the other side?

Though our stomachs were growling, we decided it would be a good idea to round the point first. The current at the point would soon turn against us, if it hadn’t started to do so already. Also the sky had darkened a bit, and there was the possibility of late-afternoon thunder. If a storm hit, we wanted to be well on our way home by then.

Plus, Vlad kept cocking an eyebrow warily at what looked like gently rolling waves off in the distance. “Those swells can get pretty big,” he remarked.

“They look like pretty ordinary waves to me,” I said. “And there isn’t much wind.”

“I’m not talking about waves, Johna, I’m talking about the swells.” I was puzzled. Waves, swells, what’s the difference? And as long as there wasn’t a lot of wind, who cared too much about either?

At any rate, we decided to round the point and look for a lunch spot on the other side. So we set off again, heading diagonally into the waves—er, swells.

Rounding the curve of Monomoy Point felt as though we were passing from a tropical summer day into a New England winter. Behind us: warm, jade-green water, with soft breezes and gently-lapping waves. Ahead: Cold water, sharp wind, gray skies—and those swells!

I quickly found out what Vlad meant by “swells”—waves created not by wakes or wind, but by the force of the ocean traveling thousands of miles before finally breaking as surf on the exposed shore.

Even when they’re no higher than ordinary waves, they pack an enormous wallop. Most of the waves we encounter in the Hudson—and even New York Harbor’s Lower Bay—are created by waves or boat wakes. They’re not swells. They can capsize you, but they don’t roll you under—and keep you down—with the same degree of unstoppable force.

And this day the swells seemed determined to keep me from progressing around Monomoy Point. The wind waves from the Sound and the Atlantic swells collided in a tide rip at the point—the rough water that Vlad had mentioned earlier. Vlad was far ahead, but I felt as though I was getting tossed up and down, just barely managing to stay upright, and not moving forward at all.

On the suddenly-cold water in that suddenly-cold day, caught in the teeth of the swells and seemingly unable to progress around the point, I realized how easy it could be—had been—for a kayaker to die here. Particularly in winter, when there was no place to land if you capsized and were unable to recover, and no one for miles around to rescue you if you became hypothermic.

I kept reassuring myself that it was a warm summer’s day, that even if I capsized I’d be all right. And slowly, slowly, I pulled out of the tide rip and rounded the point.

The crosscurrents diminished on the Atlantic side of Monomoy, but the swells didn’t. Fortunately, they were delightfully surfable. We found ourselves being pushed effortlessly forward by each powerful wave. Especially as we now had the wind once more at our backs, we were moving along at a good clip.

And we weren’t the only ones out enjoying the afternoon sunshine and rolling water. We saw plenty of seals frolicking in the surf, and great flocks of sea-birds.

But no humans. Or almost no humans—we corrected ourselves when we caught sight of a family picnicking among the dunes. We idly wondered how they’d made it onto the island—there was no sign of a boat anywhere. And Monomoy is a wildlife refuge, so there weren’t bridges, roads, or ferries.

The only downside was that there was no convenient place to land to have lunch. The beach ran along our left side, but it was steep, pounded by the dumping surf. A surf landing was possible if necessary, but was better avoided. So as the sun sank lower in the afternoon sky, we kept paddling along, surfing the swells, and enjoying the salt air.

Just for fun we would occasionally check our charts and GPS to see where we were, even though Monomoy was just yards off our left. The float plan was dead simple: Keep going until we saw the channel marking the north end of the island, turn left through the channel, and emerge back into Nantucket Sound.

One small problem: As the sun sank lower and lower, there was no sign of the channel at the end of the island—even though according to our charts and GPS, we were there.

In fact, directly ahead of us, a low strip of yellow-white, looking suspiciously like sand, emerged into view as we paddled forward. It looked like… no, it couldn’t be!… but yes, it really looked like… a strip of beach curving in a solid unbroken line from the island to our left straight across our path.

There was no channel—and no possible way we could have missed it.

We looked down at our charts: According to the charts—and the GPS—there was no spit of land in front of us, and there was a channel to our left.

We looked up. No channel, only land.

Down: Water ahead.

Up: Solid land.

Who ya gonna believe, me or your lying eyes?

We finally, reluctantly, had to accept the evidence of our lying eyes. Despite the “up-to-date” charts and GPS, Monomoy Island had somehow, mysteriously, become Monomoy Peninsula.

………….Marine chart ……………………………………..Reality

………….Marine chart ……………………………………..Reality

What to do? There was nothing for it but attempt a portage across Monomoy.

But where? We continued to follow the unbroken barrier of the beach north for quite some distance. The beach was so high that, from the low vantage point of our kayaks, we could not see over it to determine exactly where we were. And as we kept paddling, the GPS–set to return us to the launch site in Stage Harbor–began to point sharply backwards. We had overshot our mark, and with each stroke of the paddle were getting farther away from our goal.

We finally turned back, and anxiously scanned the beach for a suitable landing spot. We worried about two things. The first was the steepness of the beach and the dumping surf, which would make the landing itself difficult.

The second was that we had no idea how wide the island—er, peninsula—was at this point. We might have to walk for miles carrying heavily-laden kayaks.

Or so we thought. As we studied the beach again, Vlad suddenly shouted, “I see masts!” Sure enough, there they were: Poking up from behind the beach barrier just in front of us. That meant Monomoy had to be pretty narrow where we were—which meant our portage wouldn’t be too bad, if we could land.

And fortunately, just here a stretch of beach slanted upward—but not too sharply. No rocks. There were some lively waves crashing against the shore—but they didn’t look too high.

I went first, paddling fast to keep momentum. My adrenaline was pumping, and I was praying that I would land safely and wouldn’t end up breaking an arm. (Why did I think of that? Who knows.) I rode the waves into shore, and landed perpendicularly into the sand. I’d made it!

I sat for a moment in the kayak, enjoying the rush of success.

Big mistake!

The next round of waves slammed into me and twisted the boat sideways, trying to roll me into the sand. I wrestled my way out of the boat and found myself between the shore and the boat, which was getting pulled out to sea. I reached out and grabbed it with both arms.

The next round of waves slammed the boat into my arms, almost knocking me over. The paddle broke free and started drifting out to sea, along with my chart. But I didn’t care. I had a spare paddle lashed to the boat, and I could buy another chart. I hung onto that boat for dear life as the Atlantic swells hammered it into my arms (which were beginning to go numb).

Finally I was able to drag the boat up the steep sand.

Meanwhile, Vlad had landed, and retrieved my paddle. I dropped the boat and went after my chart, which I also managed to retrieve from the swirling foam.

So after an exciting few minutes, we were all safely ashore: Me, Vlad, boats, paddles, and the chart.

And I’d had hammered into me (literally) the first rule of surf landings: Never get down-surf of your boat.

Or as I put it: The order should be wave, Johna, boat. Not wave, boat, Johna—because then the wave slams the boat into Johna! (Actually, the first rule of surf landings should really be: Don’t sit around in your boat once you’ve landed. Hop out as fast as you can—on the surf-side of your boat—and drag it ashore.)

“Are you okay?” Vlad asked. I checked myself out. My arms felt funny and a little tender, but nothing appeared to be broken. (Later I would find myself sporting a spectacular matched set of bruises on my upper arms.)

After we’d regained our equilibrium a little, we took the few steps to the top of the beach, and saw what lay beyond for the first time. There, fortunately not far away, lay Chatham Harbor—with the boats whose masts Vlad had seen earlier gently swaying in the breeze.

The portage proved to be short and easy, downhill across sand and reeds.

And we launched into what seemed to be another world. Instead of the pounding surf, cold water, and sharp winds we’d left behind us, we were once more back in the land of warm, calm water and gentle breezes.

The sun was low in the sky as we paddled home. It took another hour or so to make our way back, threading though the maze of shoals and sandbanks. But the trip was calm and uneventful.

The most exciting wildlife we saw were kiteboarders farther out in the Sound, where the wind was stronger. We watched their graceful kites soaring across the sky and felt happy and safe.

A little while later, as the sun was setting in a golden glow, we paddled slowly past the lighthouse into the same little harbor we’d launched from.

At the takeout, Vlad chatted to a man who was working on his sailboat. Vlad told him about our trip: how we’d planned to circumnavigate Monomoy Island—had in fact circumnavigated Monomoy Island—but were chagrined to find that it wasn’t an island. The man said, “You found out the hard way, did you?”

Apparently, a big storm several years ago dumped vast quantities of sand at the end of the island, transforming it into a peninsula and creating the continuous barrier beach we’d seen. In subsequent years the sand had piled up still further, with grass and even low bushes beginning to take root. There had been talk about dredging and reopening the channel, but nothing had come of it.

So Monomoy hasn’t been an island for several years, and probably won’t be again for many more—until another big storm comes along—despite what is shown on the charts, and the GPS, and even Wikipedia.

As we washed and loaded the boats onto the car, I reflected on what I’d learned. Now I know the difference between a swell and a wave. And I don’t look at charts the same way: When there are shoals, I envision shallow water. At the tip of land, I picture rushing currents and tide rips.

And most importantly, never again will I quite believe that what I see on the chart is what is actually there.

________________________________________________________

Notes:

Kayakers dying on Monomoy: Vlad was remembering this incident in October 2003 when two women got lost in fog and died. Their kayaks, and later the body of at least one, were found off Monomoy Point in rough water, but they could also have died elsewhere and drifted there.

If you are inspired to kayak Monomoy, bear in mind also that where there are seals, there are sharks. The waters around Monomoy seem to have attracted numerous great white sharks in recent years. Boaters and indeed kayakers have come across great whites dismembering seals on several occasions.

In past kayakers’ trip reports, the kayak circumnavigation of Monomoy has generally been considered to be a challenging, but quite feasible trip. There are numerous accounts of its successful accomplishment—for example, this one from 2005. So Monomoy must have been an island as recently as that… (This report also notes that guidebooks say that “most marine charts are not accurate as to location of sand bars and breaks that have occurred in the island in the last decade.” :-))

Indeed, Monomoy must have been an island even more recently than 2005. In Google Maps, zooming in on Monomoy shows a recent satellite image in which Monomoy is clearly already a peninsula (below left). But zooming out shows a different satellite image in which Monomoy is still an island (below right). Google Maps probably updates these images every few years…

Likewise in Google Earth, zooming in on Monomoy shows a nice progression in which the barrier beach that stopped up makes first a ghostly and then a more solid appearance:

The photos in this post and other photos from our 2011 New England paddling trip are here.

I believe that Monomoy reconnected with the mainland during a storm in November of ’06. My MIL lives in Chatham so if my memory is wrong I am sure she will correct me! Sounds like an adventure!

LikeLike

Did you ever get a response from your MIL? November of 06 or 07 seems about right, if I’m correctly recalling the sailor’s comments. Would be interesting to know in the context of the Google Maps photos….

LikeLike

She says that it was ’06 right around Thanksgiving.

LikeLike

Thanks! Good to know for sure.

LikeLike

Thanks for this post. Its another adventure that I found gripping – another example of excellent writing and illustrations. It did seem much easier than your New York ones but the sea is treacherous. The tip of the Cape in Provincetown has a beach so steep that it goes from an inch to ten feet in about one foot! We love the Cape and plan to move there in our retirement — which is now. Only thing holding us back is our house which refuses to get sold. We spend a few weeks on the Cape each year and Monomoy is a destination we think about but have never gotten to. We are landlubbers but thought we’d take an Audubon tour — but now I wonder if we can walk out. I’ll look into it — its a wildlife sanctuary and Audubon is pretty strict so I’m guessing walking in might be a non-starter. But there usually is a way.

LikeLike

I’m loving that word “gripping”. Thanks so much for the good words! Good luck with the house sale–depending on where you live, the real estate market appears to be recovering, so fingers crossed!

LikeLike

Just found the US Fish & Wildlife website for Monomoy http://www.fws.gov/northeast/monomoy/ — Looks like only a few areas are off limits and only during nesting season. Great — we will go once the weather warms up a bit.

LikeLike

Thanks for that useful link, Frank! Yes, it looks like most of Monomoy is accessible—good to know.

We saw quite a few people walking along the northern part of the barrier beach, close to Chatham. Farther south people were sparse. I seem to recollect one or two but they may have landed from motorboats that we saw anchored on the Nantucket Sound side of the narrow Monomoy neck. All in all, Monomoy was pretty deserted. And this was in July; in winter it must be intimidatingly desolate.

LikeLike

very well written I felt like I was paddling along with you. makes me long for summer!

LikeLike

wonderful vicarious adventure, thanks MJ

LikeLike

You are both such adventurers! Even with all the travels and adventures I’ve experienced, I can’t even imagine doing what the two of you embrace with such grace and humor. Thanks for sharing these exciting trips, at least I get to enjoy them from the comfort of my home!

LikeLike

Thanks kadell, mj and composer! It’s really gratifying to know people read and appreciate these!

LikeLike

So easy to forget how beautiful it is up here :)

LikeLike

Pingback: Kayaking Gold on Cape Cod Bay | Wind Against Current

Pingback: Sea Kayaking Adventures in New England: A Few Photos to Start With | Wind Against Current

Fantastic post! Successful adventure and lessons learned.

LikeLike

For it to be an adventure, something has to go wrong… and it usually does!

Thanks for following our blog! I see you have your own kayaking post(s) there—will have to read them carefully :-)

LikeLike

Pingback: Travel Theme: Beaches | Wind Against Current

Wow, that’s quite an adventure. I thought the “boring” side of the island sounded pretty good. :)

LikeLike

It was good, but boring ;-) Isn’t that how it always is? The Devil gets the best tunes…

LikeLike

Pingback: Weekly Photo Challenge: Good Morning! | Wind Against Current

Nice post! love your descriptions and was completely there without the stills.

Look forward to more like this. Cheers

LikeLike

Quite a few on the blog already… but many more to come, we hope!!

LikeLike

You story was exhilarating and also gave me true chills. I will always be waving from the beach. Glad you had such and adventure and a happy ending.

LikeLike

Thanks vastlycurious! It was fun.

I’m still bummed we never got lunch though. Although if I remember correctly we stopped at a seafood place on the way back and had fried clams :-).

LikeLike

Fantastic story Vladimir – must have been exhilarating when you realized you’d finally accomplished it!

LikeLike

Thanks, Tina! And thanks for posting.

LikeLike

Wow, that is something. Sounds like the making of a movie screenplay except it is real life! Yes, grateful all ended well.

LikeLike

Me too :-). Thanks for reading, and posting!

LikeLike

Dear lands! Your ‘adventure’ put the heart across me, as they say! Now, I always thought a shoal to be a school of fish and I was expecting them to surround your craft blocking the entire area, preventing you from making progress..so I read on……Oh! you dear, but scaringly adventurous, persons.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s strange when you realize you THINK you know what a word is, and it isn’t. I guess I’d heard the phrase “rocks and shoals” so many times that I’d conflated them–maybe you did the same thing with “fish and shoals”, or something? Anyway, thanks for reading–and posting!

LikeLike

outstanding!

LikeLike

Thanks!!

LikeLike

Was sent here by Vladimir’s “Good Morning” post. Glad he posted the link… captivating and informative writing. Glad your injuries were limited to bruising. Hope to be kayaking in the Gulf later this month. No seals but have had several experiences with pods of dolphins.

LikeLike

Thank you!

Which side of the Gulf? Texas or Florida? (I guess there’s also Louisiana!). I’ve been out in the Gulf on the Florida side, but my one attempt to make it to the Gulf on the Texas side ended rather badly–that was before I understood the hydrodynamics of channels and inlets!

At any rate, happy paddling!

LikeLike

We vacation on the Florida panhandle where the waters can range from lake placid to 2-3 foot waves in a matter of days. Weather permitting, we kayak everyday of our two weeks there. I, too, learned the “first rule of surf landings” after suffering some nasty bruises to the shins. For me, kayaking is a once-a-year experience, so always enjoy seeing your posts!

LikeLike

I was once knocked over by a tiny wavelet that picked up my boat and surfed it shoreward where I was standing in about six inches of water… Once that boat starts moving, it’s hard to stop—all you can do is get out of the way… :-)

Thanks!!

LikeLike

Pingback: Everglades Challenge, Segment 3: Magic Key to Indian Key | Wind Against Current

Pingback: Everglades Challenge, Segment 6: Flamingo to Key Largo | Wind Against Current

Pingback: On the Way | Wind Against Current

Marvelous post, pictures, words, and all!

LikeLike

Thanks!!

LikeLike