A few days ago we posted “Thanksgiving Musings: We’re Grateful for that Still, Small Voice…,” in which we referred to a wonderful essay by writer and adventurer Willis Eschenbach. He generously gave us permission to reprint the essay in full on our blog. Here it is. We hope you enjoy it as much as we did!

Guest Post by Willis Eschenbach

With Thanksgiving coming up, I thought I’d write about something other than science. A few weekends ago, I went by kayak across Tomales Bay from Marshall to Lairds Landing, where I lived for nine months or so when I was about twenty-five with a wonderful friend and his lady and their son. It had been fifteen years since I was last there, I’d gone for the wake not long after my friend died. I went on this trip with a long-time shipmate of mine, a gifted artist, builder, and blacksmith.

Now, there are lots of words for the gradations of friendship—friends, acquaintances, work-mates, BFFs, room-mates, colleagues, and the like. “Shipmate” means more than any of those to me. It means someone who I’ve been through some storms with at sea.

A shipmate is a relationship based on the fact that at sea, when I go to sleep, I place my life in my shipmate’s hands. And in the same way, when he sleeps he depends on my vigilance and ability. It is a relationship based on dangers faced, storms survived, and obstacles overcome through teamwork and mutual support. A shipmate is someone who I have lived cheek to jowl with, someone whose actions and moods and strengths and weakness are as clear to me as mine are to my shipmate. A shipmate is someone I can wake up early if I’m three-quarters of the way through my midnight-to-four watch and I can’t stay awake no matter what I do, and he dresses and comes on deck with no word of reproach, checks the course, eyes the sails and the wind, takes the helm, and tells me to get some rest, he’s got it … just as he knows I’ve done for him and would again. A good shipmate is a rare thing and a treasure.

In any case, my shipmate had a great history with my friend at Laird’s Landing as well. I’d introduced them, both artists. It was a journey of remembrance for him as much as it was for me. So we tossed the kayaks on his truck, and put in at Marshall. Tomales is a bay with a curious geological history. You know the famous San Andreas fault, the one that caused so much damage in the 1906 earthquake? Well … in the aerial view, you’re looking at it. It runs right down the middle of Tomales Bay. The land on the west (left) side of the bay was once off of LA and (like many Californians) moved north from there. The plants and ecosystems of the land on the left are often different from that on the right.

We paddled across a choppy sea, wind in our face and low fog overhead. There were some whitecaps, what we called “popcorn” when I was a commercial fisherman, but the wind was fresh rather than strong. It was good to come on the place slowly, by boat, just as I had done so many times back when I’d lived there. As we neared the shore, I saw one thing I’d forgotten, the string of small sea-level caves. At one certain stage of the tide and wind, the small bay waves transform the caves into a natural musical instrument. They break across the mouth of the caves, and each one emits an unearthly bass note, with the pitch of the note determined by the size of the cave. When a number of them got going back in the day, I could hear them in my little sugar shack up on the hill above Clayton’s place. Here’s how that all came about.

After my girlfriend and I split up around 1971, the house on the land we’d bought seemed empty. I was hitchhiking one day near the south end of Tomales Bay and I was picked up by an old guy who introduced himself as Clayton Lewis. At least he seemed like an old guy when I was 24, although in fact he was only about 55 at the time. As we were riding along, he mentioned that needed some help with a big piece of oak he had in the back. I offered to help him. We went to the shop of a guy named Blind John, who was a blind boatbuilder in the town of Point Reyes on Tomales Bay. No kidding. Clayton introduced me to him. The guy was stone blind, but he built beautiful boats. His hands were like living creatures, ceaselessly exploring the world around him.

Clayton was a renowned artist and he knew all the really good artists and artisans and craftsmen in the area. We hauled the piece of oak into John’s shop. John had a big bandsaw, Clayton only had a small one. John came and ran his hands over the piece, his restlessly moving fingers questing, appraising the wood. He asked Clayton what it was for. Clayton said he was cutting out a new stem for a Monterrey boat that he was rebuilding. I said I’d fished on Monterrey boats, it was a boat design I loved. Clayton said he was fishing commercially in Tomales Bay. Intrigued, at his invitation I went out to see his place.

Clayton lived in one of the world’s lovelier spots, “Laird’s Landing”. It is a small cove, with a beach, on the west side of Tomales Bay. It was an inholding, surrounded on all sides by the land of the Point Reyes National Seashore. Clayton had a “life estate” on the property. Twenty-five years later, after his death it became part of the National Seashore.

I became close friends with Clayton, and after a few months I put my house and property on the market and moved out to a tiny sugar-shack I built at Laird’s Landing. (My property finally sold a year later. I contacted my girlfriend and sent her half the money. That was the deal and she had more than fulfilled her part, she’d worked as hard as I had on the land and the house.)

Clayton was an artist, and a jeweler, and a boatbuilder, and a fisherman, and a crusty old bugger. He owned three boats, all of them with beautiful lines. I was going to buy a boat once, because it was cheap, even though it was ugly. “Don’t buy it,” he warned, “owning an ugly boat is bad for a man’s spirit.” I didn’t buy it, and I definitely added that to my rules of thumb.

He and his good lady, Judy Perlman, were both jewelers. He’d learned a lot of the art from her, her work is awesome. So I got to learn a lot about jewelry as well. Living with Judy and Clayton and eight-year-old Marcos Lewis for almost a year was like going to the finest boatbuilding/fishing/art/sculpture/woodwork/jewelry school in the world.

For years Clayton had fished one of the world’s most romantic fisheries. It was a night fishery using what’s called a “beach seine”. Clayton had a gorgeous, hundred-year-old ship’s longboat from San Francisco. It had been built in the 1850s and used as a “wherry”, a boat to row goods and passengers to and from the ships anchored out from the piers. It had two sets of oars, with what we used to call “smuggler’s oarlocks”. These are special oarlocks that, unlike the regular kind, are perfectly silent in use. On that boat we used them to avoid scaring the fish, rather than to avoid alerting the Coast Guard.

We’d set out after dark, with both of us wearing hip boots, both of us rowing, and we’d pull for one of the nearby beaches. Tomales Bay is long and narrow with a bar across the mouth, so there’s rarely a big swell. We’d row into the beach. I’d jump out and run the net anchor a little ways inshore from the water’s edge, bury it in the sand, and get in the boat again. As we rowed back out, the anchor rope would start pulling the net off of the back of the boat. We’d set the net in a semicircle, and return to the beach some distance from where we started. Our net had floats at the top, and leads at the bottom, and it now walled off that entire section of the sea. I’d jump out and run down the beach to where I’d set the anchor. Clayton and I would start pulling the net up on the beach and walking towards each other. Eventually, all the fish were in a small area of net in the middle. We’d take out the fish we wanted and let the rest go.

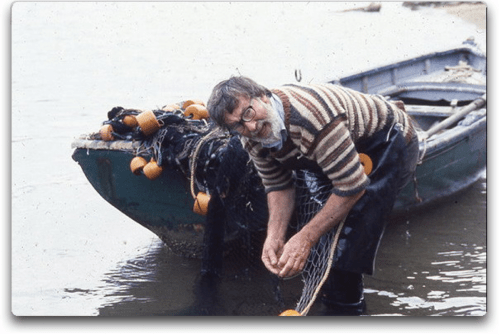

We were fishing for surf perch, but because the net walled off that section entirely we’d catch anything that was there. Stingrays were the most common species besides perch. Some nights we’d catch ten or twenty in every set of the net. We’d pull them aside, take out the fish, and put the stingrays back in the water. Clayton and I were both advocates of disturbing the ocean as little as possible consistent with commercial fishing. We’d pull the rowboat alongside the net, and put the perch, sorted by species, into boxes, along with the odd flounders and other fish that we could sell. Then we’d release the small fish and the ones without commercial value. Here’s His Crustiness at his finest, with the century-old boat we used …

After releasing the fish we didn’t want, we’d walk the boat down the beach in the shallow water. Stack the nets back in the boat, walk up the beach and get the anchor, break out the oars and move on to the next set of the net. In the course of a night we’d do four or five sets.

Then we’d row back to Laird’s Landing and catch a little nap. Get up at six am or so, load the fish into Clayton’s truck and we were off to where Clayton had always sold his fish Chinatown in San Francisco. Now, I’d sold fish in Chinatown before, and I wasn’t sure how I’d be received … here’s what had happened. Some years before, I’d worked as a crewman for a Sicilian guy named Sam Mazzerino, and we sold our fish in Chinatown.

Now, doing business with Chinese folks hasn’t always gone in the direction I expected it to take. There’s always some curious twist in the story. We’d put the fish in the back of Sam’s truck and drive up to Chinatown in San Francisco. Sam knew all the merchants. We went to the first one. “How much-a you pay,” Sam said. He actually talked like that, like some Italian in a cartoon. “Fi’ cent” came the answer. “Five-a cent! Last-a time you give ten”. I eyed the young Chinese guys cleaning and gutting fish while Sam talked to the owner. They all used razor-sharp cleavers. A cut, a slice, a few well-aimed chops and it was done.

One day, after weeks and weeks of this same stuff, Sam couldn’t take it. He stomped out, irate at the eight cent offer for Extra Medium pompano or something. We went to the next guy. “Seven cent,” he said. The next guy said six. We went back to the first guy. He offered “fi’ cent”. We went on the street. Sam swore in Sicilian, unusual for him, I could see the steam coming out of his ears. His usual big swear was “Jesakreisalminey”, which was so slurred it had taken me a week to translate to “Jesus Christ Almighty”. He pulled over and parked in the street. He opened the back. He said, “Sell-a quick, boys, we no gotta much time. ” He sang out “Cheap-a pompano! Caught last night! Fresh Pompano!” Immediately we were swamped in a tide of Chinese housewives, a shopping rugby team which gives no quarter. The crowd kept growing and pressing in on us in a Chinese scrum. We charged a dollar a bag, we charged a dollar for three fish and a dollar for five fish. We gave no ground, we offered no change. At some point, Sam tapped my arm and pointed.

Three Chinese guys were leaning against a storefront. They all had their fish buyer aprons on. They all had their razor-sharp cleavers that they were rhythmically slapping against the palm of their other hand. They were all looking at us. One of them silently pointed down the street. We nodded. We shut the back door, and drove out of Chinatown.

Anyhow, when Clayton and I went to Chinatown, I saw the guy who was the “fi’ cent” man, but I guess he and the guys with the cleavers had forgotten my face, there was never a problem. We’d sell the fish and drive home.

But that’s just what we did for money. The main thing we did that occupied most of our time was the rebuilding of the “Angelina”, Clayton’s Monterrey-style wooden commercial fishing boat. It was about 26 feet (8 m) long, with the sauciest lines imaginable. It had fallen on hard times, there was rot, planks were gone. Over the course of about a year, Clayton and I rebuilt that boat. I should say Clayton rebuilt the boat, and I worked with him throughout. He was a genius of a boat builder. Most of what I know I learned from him.

By training, Clayton was an artist and a sculptor, he’d been to school for that, his works were valuable then and are more valuable now. His artworks are in the permanent collection of the LA Los Angeles County Art Museum, in the French Postal Museum in Paris, and the California Historical Society in San Francisco. His bed, the bed he slept in when I lived at Lairds Landing, is in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His bed. That’s how deeply his art was intertwined with his life.

When we kayaked out there, we looked in the small house where the bed was. My shipmate wondered where it had gone. When I told him it was at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), he cracked up. When he’d stayed with Clayton at Laird’s Landing with his girlfriend, that had become the guest bedroom … so the very bed where he and a lovely woman had made great sport in his younger days was now in the Museum of Modern Art. As an artist he found that priceless, he said it was likely the only way his DNA would ever end up in the MOMA …

My shipmate and I and Clayton had sat and laughed and talked story many times in the main house, now fallen to ruin, gone along with the guest bedroom shown above. Since Clayton’s death the place reverted to the park, and now it’s fallen to pieces and scrawled with graffiti … but even so Clayton’s spirit lives on, even the graffiti are not your usual:

He brought his artist’s eye to his boatbuilding. An example was the piece of oak I’d helped him cut the day I met him. It was for the stem of the Angelina. The stem is the “S” shaped piece of wood at the very front of the hull of the boat. All of the planking of the boat comes together at the stem. It has a subtle 3-D shape.

Clayton had simply gone out into the woods and cut a large oak limb that had exactly the shape that he needed. I asked him how he’d done it. Clayton often measured things with knots in a piece of string. He said he’d measured the length he needed with a piece of string. But how did he measure the shape of the limb, I asked, to make sure it would fit the complex curve?

Oh, he assured me, he’d just taken a look at the old stem and sketched the curve. It was too heavy to haul around in the woods himself, so he’d just looked at it with his trained sculptor’s eye for shape, drew it on paper freehand with a blunt carpenter’s pencil, tied some knots in a piece of string, walked out in the woods, and looked at his sketch and measured with his string until he found a limb that looked the same. Easy.

He knew all the old ways to do things. Most guys steam-bend wood using, well, steam. They have a boiler where the water is boiled, and then insulated pipes carry the steam to a wooden or metal box. The box is filled with the pieces of wood to be steamed, the cover is put on and the boiler fired up. Soon the steam heats the oak. Oak is great for steam-bending, when it gets hot it bends like rubber, it’s amazing to see.

Clayton scorned all that complexity, he just boiled the oak. He had an old piece of 16 inch (400 mm) steel pipe. He welded a piece of flat plate to cap off one end of the pipe. He welded a couple of legs on the other end, to hold it up off the ground so it sat at an angle. He put it down by the beach and filled it up with sea water. He said sea water was better than fresh because it boils at a higher temperature. He’d put in the oak he wanted to bend, and then build a fire under the pipe. After while the water would boil. He’d cook them good, then pull them out of the boiling water and bend them to the desired shape. Old school ways, Clayton knew them all.

Alas, in my world even the best of projects have a fixed ending date. In my case, I’d moved out to Laird’s Landing to help Clayton rebuild the Angelina. Finally, most of the work was done. Clayton hated engines, he much preferred oars and horses. So I’d rebuilt the engine, and gotten it started, and tuned it up. Now, even that was done, the engine was running sweetly. The new planking was in and fastened with boat nails, the seams between the planks were caulked, everything was painted. I’d learned from Clayton how to caulk a boat the old school way, with oakum and a caulking chisel, listening for the sweet ringing sound of the chisel that means the seam is filled perfectly. She was painted and tarted up like the San Francisco waterfront lady she’d been in her youth. Clayton had carved a sternboard with her name, and carved the bowsprit (the short wooden pole sticking forward from the frontmost part of the boat). The tiller for steering the boat was a gorgeous example of his art, lovingly sanded smooth and sensuous to the touch of the helmsman. I learned that indeed, having a beautiful boat was good for a man’s spirit. We had launched her and put her through her sea trials, and she was anchored off the beach. We used her for a couple of months to avoid the long tiring rows to distant fishing beaches. We’d go to those beaches in the Angelina, towing the rowboat behind. Then we’d anchor the Angelina and fish from the rowboat. Modern luxury.

I can’t tell you how much I learned from Clayton, including a curious rule of thumb. I live my life in part by rules of thumb that I’ve learned over the years, rules that help cut through my confusion. One rule I got from Clayton. I asked him how much rent he paid for Lairds Landing, which comprised I think fourteen acres, two houses, the jewelry shop, the sculpture and metal casting shop, and a detached bedroom, the well, the garden area, all in a secluded cove surrounded by Point Reyes National Seashore.

He said he didn’t pay any rent at all. He stayed there for free. I was shocked. I asked how he found it. He said it wasn’t all that hard. He said when you’re looking for places to live that are cheap, you have all this competition. Everyone wants to find a cheap place to rent. But when you look for a place that’s free, almost nobody is doing that, so you have the field to yourself. I noted that as a valuable rule, “When you look for the unusual, there’s not much competition.”

Clayton and I parted the best of friends, and remained that way until his death a quarter of a century later. His official website is at here, with a picture of the crusty old man on the front porch of his house at Lairds Landing, and many examples of his amazing art. Judy moved to New Mexico and is still producing gorgeous jewelry. Her web site is here, worth a look. And their son Marcos, true to his blood, is an amazing potter. In addition to learning about jewelry and life from Judy, the rule of thumb I learned from her was, “Men sweep round rooms”, meaning that in menial tasks we missed the corners in both a physical and metaphorical sense … and I could hardly argue. I use that rule of thumb to move myself to sweep the corners.

But the job was done, the Angelina was bobbing happily at her mooring just off the beach, and it was time to move on. I said a fond farewell to Clayton, to Judy, and to Marcos, and went down the road. I had no money saved up, so I took a job as the summer assistant to a “shade-tree butcher”. That’s a guy hired by the farmers and ranchers to come out to their land and kill and butcher up one of their animals. Then we’d either put it in the farmer’s freezer, or take it to the cold storage meat lockers at the butcher shop. For the next three months or so I handled more cow guts and pig intestines and sow’s ears and hides and various animal parts than you can imagine … but at least I could save my money. So when the fall came and the job ended, I retired again, and I hitchhiked down to the border and crossed over into Mexico … but that’s another story, this one’s done.

A warm and welcome Thanksgiving to all,

w.

What a wonderful remembrance!

LikeLike

Thanks, Lois–I’ll let Willis know!

LikeLike

Great story of a true friend…

LikeLike

Glad you liked it!

LikeLike

What a pleasing essay – and what a pleasure to be introduced to Clayton Lewis and his envelope art and to Judy Perlman and her jewelry!

LikeLike

Anna, so happy you liked it. And Clayton and Judy!

LikeLike

What an adventure to read. I was thrilled and entertained. Thank you!

LikeLike

You are most welcome! I’ll let Willis know.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed your partial auto-biography and the story! Such an interesting life Vlad!

LikeLike

Just to be clear, this isn’t Vlad: The author is Willis Eschenbach. And yes, he does have an interesting life!

LikeLike

beautifully written, Willis Eschenbach is very talented. thank you Johna for sharing it!

LikeLike

On behalf of Johna: You are most welcome!

LikeLike

Thanks for the great kayaking thoughts. Kayaking is a great activity.

LikeLike

I couldn’t agree more! Thanks for reading, and posting.

LikeLike

Thanks for the nice article and images to both Willis and Johna.

LikeLike

Double thanks to Willis, our first-ever guest blogger! And thank you for posting!

LikeLike

Actually, our second guest post—we mustn’t forget Kayak Cowgirl’s guest post :-)

LikeLike

Of course! And what a fine one that was…

LikeLike

Thank you for this guest post… wonderful story and well told!

LikeLike

You’re most welcome, and I agree!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a beautiful story. What a gift it was to have Clayton, Judy and Marcos a part of your life. Thanks for sharing, your story gives a lot of food for thought on the important things in life.

LikeLike

It is indeed! You are most welcome—thanks for commenting!!

LikeLike