Bronx lights

by Johna Till Johnson

Photos by Anonymous

Note: I wrote the below in “before times” (before Covid).

I’m a law-abiding sort, the kind of person who pays taxes on time and in full, and who doesn’t like to cross the street against the light.

I also have a great imagination.

So when my friend R. handed me a USB stick with photos from an anonymous source apparently taken on Hart Island–where it is highly illegal to land and even more illegal to explore—I couldn’t resist imagining how an exploration might have gone down, had anyone been reckless enough to risk it. Here’s my imagined version:

“Directions to….unknown location on unknown street?” Google Maps asked.

It was fitting: I was on my way to a waterfront warehouse somewhere in Brooklyn to meet my friend R. for a clandestine expedition—so clandestine that even Google Maps couldn’t discern the starting location.

It was just after dark on a Saturday evening in late summer. The plan for the excursion had come together with surprising speed, in one of those serendipitous ways that just tells you the universe works mysteriously in your favor.

We were supposed to be doing a different expedition, a trip down the eastern coast of Staten Island. But then R. sent me a tantalizing note: “Text me on encrypted channel? I’ve got an idea for a mission I don’t want to talk about.”

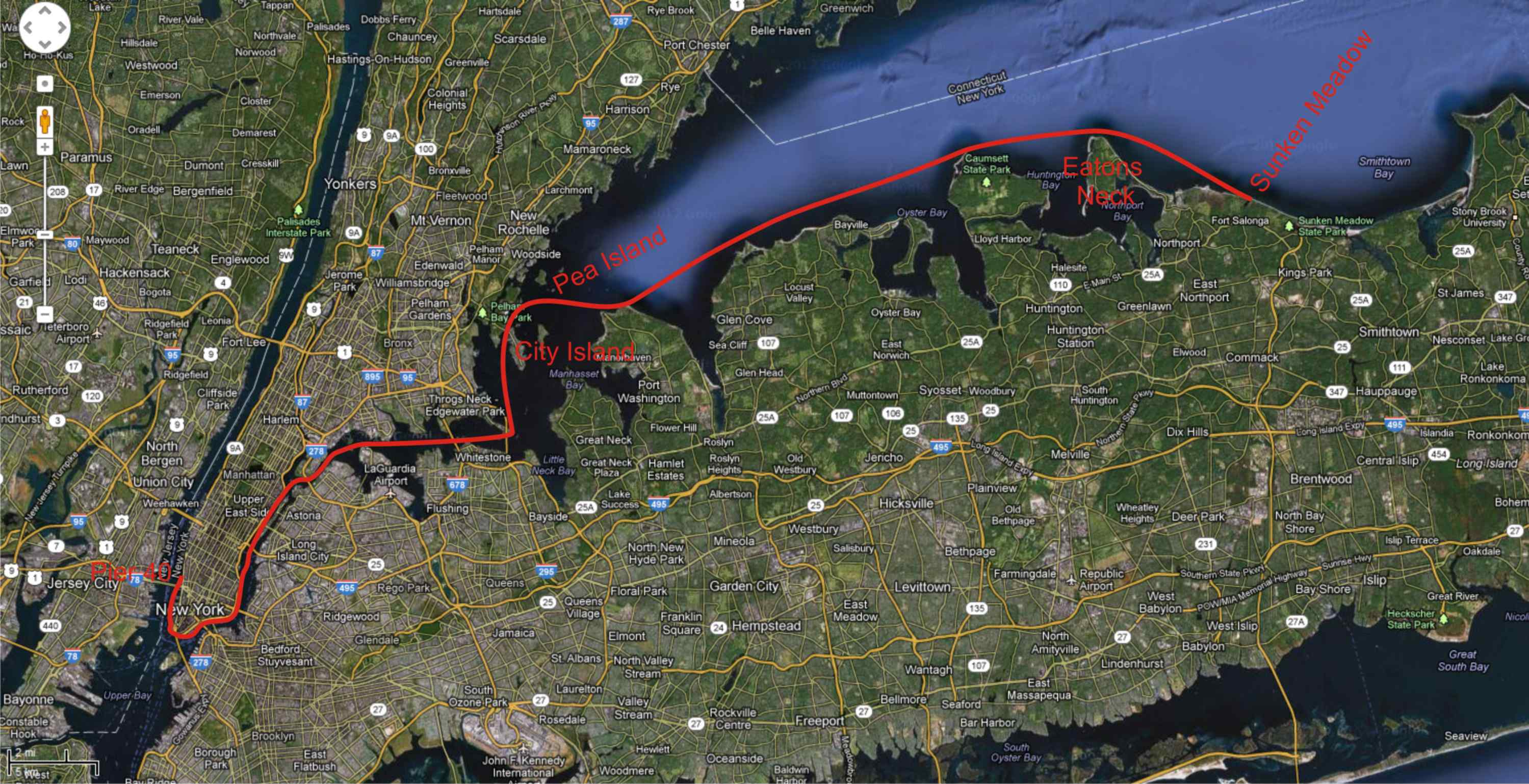

We connected, and he shared his idea: We would launch from someplace in City Island, paddle to Hart Island and explore.Hart Island has a long and storied history dating back to pre-revolutionary times. It currently serves as New York’s Potters’ Field, where the bodies of those who died unclaimed lie in rest. They are buried by prisoners from Riker’s Island, who arrive each morning on the ferry, and depart at sundown. The island is uninhabited by humans—other than the approximately one-and-a-half million dead—from sundown to sunrise.

Most NYC-area kayakers harbor a secret wish to explore Hart Island, due to its mystery, its historical significance… and also because it’s tantalizingly available yet completely forbidden. For complicated historical reasons, it’s managed by the Department of Corrections. Trespassing on the island is trespassing on prison property, and carries a two-year prison sentence.

Vlad and I had landed on Hart Island many years ago and had lunch on one of the beaches, but I’d never gone further, out of fear of the authorities, and also out of respect for the dead. There’s an air of sadness over the island. Anyone who lies buried there was alone at the end of his or her life, so each grave marks not just a death but a person whose life ended in loneliness and disconnection.

And that life may have been tragically short: Among the graves on the island is that of the first baby to die in NYC of the then-new AIDS virus in the 1980s. He or she lies buried at the southern tip of the island, in a special area apart from all others. The authorities didn’t understand AIDS then, and feared contact even with the corpse of a baby.

This might be the last chance for such an expedition. R. explained that in October a massive renovation would launch, shoring up the crumbling beaches eroded by storms.

Apparently during superstorm Sandy in 2012, bodies had washed out into Long Island Sound, ending up on the beaches of well-off waterfront property owners.

There were complaints.

After several years, the city eventually decided to take action. Details are few, but as part of the renovation they will probably wall off the shoreline, wire the entire island with surveillance cameras, and generally bring it from the 19th into the 21st century. And it would all start in a few weeks.

So this was it: a now-or-never moment.

“I’m in,” I said.

Then I realized he meant we’d go at night.

Wait, what?

How would we see anything?

And… seriously, explore the largest cemetery in the country at night?

But I quickly realized R. was right. If we wanted to avoid detection, it would have to be at night. If it stayed clear, we’d have the light of the gibbous moon, and we’d have red-spectrum headlamps.

There was more: R. had been planning this trip for a while. He had two Ghillie suits, unworn and ready to go.

Ghillie suit

Snipers and hunters wear Ghillie suits to avoid detection. “You really can’t be seen, even in they shine a spotlight on you. They’re amazing!” R. said.

What he hadn’t said was that you look like Chewbacca covered in Spanish moss when wearing them. And they catch branches and leaves while you’re walking until you feel like you’re part Ent. But that comes later…

We planned to meet up in Brooklyn around 9 PM, then drive out to City Island. We’d locate an acceptable launch spot, paddle out, and explore, making sure to be gone by dawn.

So far all was going well.

Google Maps navigated me efficiently enough to “unknown location on unknown street” on the Brooklyn waterfront. Sure enough, R. was waiting. We drove off into the quiet Brooklyn night, lit by the lopsided moon in a clear dark sky.

When we got to City Island, we were confronted by an unexpected challenge. Both of us had landed by kayak at City Island at various times over the years, and R. had launched from there more than once. We both had firm recollections of streets dead-ending onto open beaches, so we hadn’t really worried about finding a launch spot.

But this time, inexplicably, there were none.

For over an hour we explored City Island street by street, only to be confronted with high fences and “Private beach: Keep out!” signs blocking the waterfront access.

After about ninety minutes we’d located a couple of places that weren’t entirely insurmountable; although clearly labeled as private property, the houses nearest the beach seemed uninhabited and it would be possible, with effort, to maneuver loaded boats around and over the barriers.

But both of us were uneasy about the idea, and we kept looking, although our hopes were fading rapidly. Suddenly, R. squinted into the darkness ahead of us. “Wait, is that a Jersey barrier?” he asked. It was. Nice and low, about two-and-a-half feet high, with one corner conveniently worn away so we wouldn’t even have to lift the boats over.

Even better: there were no “No Trespassing” signs. The buildings adjacent were dark and seemingly unoccupied. And the neighborhood had plenty of parking.

We parked and loaded up the boats. Deck bags. Cameras. Hiking shoes. Jacket in case it turned cold. Water. And the Ghillie suits.

Soon we were launched and paddling the moonlit waters of Long Island Sound.

It was a calm, warm night, and the water was clear as glass. The stars, nearly invisible from midtown, twinkled brightly over the Sound.

We kept lights and radios off, but our eyes quickly adjusted to the dim light. We could track each other’s shadowy profiles in the dark.

It was only about a mile to Hart Island, but in the calm night, hearing only the splash of our paddles and the muffled sounds of traffic from the Bronx behind us, the trip seemed to last forever.

Finally we pulled the boats up on the beach. Just as I’d remembered it from a decade before, there was the wreckage of a large motorboat at the north end of the beach.

“We can hide the boats there,” R. whispered.

The word was the deed.

Moving as quickly as we could, we slotted the boats into gaps of the wreckage, and draped tarps over them. From just a few feet away, they were virtually invisible.

Then we changed into hiking shoes, mounted our headlamps, and pulled on the Ghillie suits, which were surprisingly light considering the bulk. They were made of fine mesh, good for keeping out insects, and would provide an extra barrier against the poison ivy R. said grew copiously on the northern tip of the island.

Then we climbed up the low hill to the grassy meadow. We were officially on Hart Island!

The first place we visited was a large white cross set into the hillside. We paused for a moment, letting the solemnity of the space sink in. Then we started walking again, and soon located a grave off to the side. We thought it was the AIDS baby’s, but R. checked the map and realized we were at the wrong end of the island.

We rounded the northern tip and looked out on the dark waters of Long Island Sound. Then we headed south.

Our steps sounded loud; we winced with each crunch and crackle on the dry leaves and sticks. But the Ghillie suits worked as advertised—even from a few feet away, we were invisible to each other in the gloom.

It wasn’t entirely dark. In addition to the moon and starlight, there was the electric glow of New York City low on the horizon. And when we turned on our infrared headlamps, the glow took on a rosy tinge.

But our lights weren’t on when I caught sight of something glowing, just behind my right shoulder.

“R.!” I whispered urgently. “There’s a ghost!”

“I believe it!” he said. For the rest of the evening, I felt the presence and faint glimmer of… something….someone… following behind me.

We stopped to admire a square white obelisk set on a platform, inscribed with a white cross. It was the peace monument, erected by prisoners and staff in 1948 to commemorate those interred on the island (see this account for a brief description.) We continued on. The night swirled with strange gusts of air: at one moment it was cool enough to make our skin prickle, the next warm as if from an oven opening.

“I’ve got chills,” R. whispered. “Me too,” I replied. I couldn’t stop thinking about the million-and-a half people who died alone, either unloved or unfound by frantic friends and relatives, to lie forever in the soft earth lapped by the waters of Long Island Sound.

Memorial

We kept walking. Soon we came across a clearing, dotted with flat metal plates set into the ground. It was the abandoned Nike missile silos (See: here, here, and here.)

R. was able to move one of the heavy metal covers and peer down inside. “I’m tempted to go in,” he whispered. R. is a rock climber, capable of athletic feats I can only dream of. Still, I was glad when he decided against it.

We continued on, down the eastern side of the island. As we crunched over broken branches and swished through the tall grass, we caught sight of an American flag rippling over a rectangular plot of land, lined with white marble, on which stood a white obelisk. It was the Civil War Veteran’s Cemetery The inscription on the obelisk read: “The remains of these veteran Union soldiers and sailors were disinterred on June 9, 1941 and reinterred in the Cypress Hills National Cemetery.”

We stood quietly for a moment with bowed heads. I don’t know what R. thought, but I was imagining the men who had once been buried here.

Then we continued on, doing our best to stay close to the edge of the clearing, with forest on our left.Suddenly we heard something rustle in the woods beside us.

We froze, barely breathing.

There was a loud “thump” and then what sounded like footsteps, moving rapidly away.

“What was that?” we asked each other. Intellectually we knew it had to be an animal of some sort, possibly a raccoon; R. had been told by someone who’d worked there that there was a large population of raccoons on the island.

But still.

After a bit our heart rates returned to normal, and our palms stopped sweating. Over to the right we could see ruins of old buildings silhouetted dimly against the sky.

We kept on, steering well clear of the operations hub in the center of the island, and the ferry terminal beyond that. If there were cameras or watchers, that’s where they’d be.

We continued on. And on. Through what felt like endless stretches of darkened woods, bordering grassy meadows and walkways. I knew without asking where R. was headed. He wanted to pay his respects to the grave of the AIDS baby.

Once we were safely into the southern portion of the island, we swung inland, to the right. Up ahead loomed a ruined building, windowless. We stopped to peer inside.

R. went first. “Holy shit!” I heard him whisper. On the ledge of the open window was a thick stack of documents, thicker than the palm of my hand is wide, partly destroyed by mold.

“City of Yonkers police department, 1985” we read. R. flipped through the pages quickly, stopping at one with fingerprints of the dead.

We looked through the window, into the building.

The floor was completely covered with stacks of documents. A few filing cabinets stood, drawers open, with more documents within.

What was it? Why had the documents been abandoned? There was no way to know.

The online sources we’d visited said all documents had either been destroyed by fire or removed. But here was an entire building, open to the elements, packed with decaying paper documents.

We kept going, back into the grass and brush.

R. was a few yards ahead of me when I saw him freeze. “What was that?” he whispered. “I just heard something breathe!”

Just then, some footsteps sounded. The trees rustled. Then silence.

Whatever it had been was gone.

We continued on, until we were nearly at the southern tip of the island. Ahead of us stretched a row of white square posts, each marking the site of dozens, perhaps hundreds of graves.

“This is it,” R. said. Each one had the SC-B (Special Child-Baby) notation, indicating babies were buried there.

We moved along the line of graves, stopping to take a picture of the very first one. We’d found the grave of the AIDS baby.

But something was wrong. Wasn’t the AIDS baby supposed to have been buried alone?

“What’s over that fence?” R. asked suddenly. To our side was a high wire fence, half-covered in greenery, topped with rusting barbed wire. As soon as we made out what it was in the pale light, we realized what it must be.

We followed the fence to its end, and curved back around, so we were on the other side.

Sure enough, there was a square white marker all by itself, fenced off from the others. Its location alone told us what we’d found: SC-B1, the first to die of AIDS, then viewed as so contagious that he or she was isolated even in death.

Special Child (SC) Baby (B)-1

We took pictures, and I said a silent prayer for SC-B1, wherever he or she was.

And for the parents of the child, likely long gone themselves. For the frightened prisoners handling what they viewed as the carrier of a highly contagious, perfectly lethal disease. For all the people touched by this disease, those who died and the ones who lost them.

Somehow SC-B1, buried alone on Hart Island, encapsulated all of the tragedy and loss and fear of that period.

We turned to head back, feeling obscurely that no matter what else happened, our mission here was done.

“There’s one more thing I want to see,” R. said. “There’s the remnants of a road, and New York City streetlights.”

We went back across the long field where we’d heard the breaths and footsteps.

Although it was less than an hour ago, it seemed like a different era: Before baby SC-B1.

Suddenly R. froze again. “Look!” he whispered. “A deer!”

My eyes straining, I finally made out what R. was pointing at: The silhouette of a deer, at the end of the meadow, against the twinkling lights of city island.

That must have been what caused the breathing, and the footsteps, and the crashing through the underbrush. (We later learned that deer had populated the island for at least 200 years; at one point it was a privately owned game preserve. The deer could possibly have been a native inhabitant of the island; or possibly it swam over. )

Now that we’d confirmed there were large animals on the island, some of the mystery left. It almost could have been an ordinary walk on an ordinary meadow on a late-summer night.

But not for long.

After a few minutes, the road appeared in front of us. Concrete, running between two abandoned buildings. And there, just as R. had said, was a New York City streetlight. Just beyond it to the right was a beautiful building, with double stairways climbing up to an impressive doorway.

Just opposite it across the road, to the left, was a dark building looming with Gothic curves against the sky.

It was a church. R. loped over to inspect it. The door was partly ajar, and he slipped inside. A second later he poked his head out: “Come inside, it’s worth it,” he whispered.

I stepped in, walking gingerly over the uneven floor. It was indeed a church, a massive ruined structure. The roof was largely intact, and there was a beautiful, strangely undamaged rose window at the far end.

We later found out it was a Catholic church, built in 1932. (A fascinating religious history of Hart Island and other components of the prison system was written by Episcopal archivist Wayne Kempton in 2006; you can Google it to find a downloadable PDF.)

Catholic church from inside

We lingered for a while in the church, perhaps too long. Even in disuse, its soaring arches and echoing interior conveyed a sense of peaceful melancholy. But finally the skies outside the windows had lightened too much to ignore, and we regretfully took our leave.

By then, we were confident we’d seen most of what Hart Island had to offer.

We were wrong. As we continued through the compound of ruined buildings, we came up to a large square hole, about 20 feet on each side, rimmed with wood.

“It’s an open grave,” R. whispered.

We looked closer. There were pallets, and what might have been simple wooden coffins beneath. We knew that bodies were stacked 3 deep in each plot; this one looked to be about halfway full.

After a moment R. moved to continue on. “Wait,” I whispered. Following an inner compulsion, I bowed my head and said an Our Father. Then I made the sign of the cross over the open grave, wanting to show these unknown people in death the respect that had been denied them in life.

Then we turned and continued on.

The walk back seemed much faster than the walk down; in fact, we overshot our landing spot and went up to the tip of the island again. After we realized our mistake, we trotted down the hill that led to the white cross embedded in the hillside that we’d seen when we first started out. The sky was definitely lighter, and there was a tinge of rose along the eastern horizon.

Neither of us wanted to leave. We sat down and tried to pick out the branches and leaves that had accumulated in our “fur”, but it was a hopeless task. We’d done a lot more bushwhacking than the suits were designed for, and our artificial foliage was now augmented permanently with the organic kind.

After a bit, R. lay down on the grass for a micro nap, foliage and all. I sat and watched the sky brighten slowly, the stars dimming imperceptibly out.

Finally, when it was too bright to risk staying any longer, I told R. we needed to go.

A few minutes later, we were back in the boats, safely pushed off from shore. For the first time in several hours, we were no longer afraid of discovery: From here on out, we were just innocent paddlers.

I was relieved, but also sad. As the dark waters of the sound lapped our boats, part of me wanted to stay on Hart Island, with the graves and the ruins and the silence. But it was time to rejoin the world of the living.

We paddled back slowly, looking back over our shoulders often to catch the sunrise.

We passed a few fishing boats out from City Island. A sailboat floated past.

We were a few yards offshore when the rising sun broke over Hart Island, reflecting off the buildings on City Island.

We’d done it, something that very few living people can lay claim to have done: spent a night on Hart Island.

Departing at dawn

Note: If you’re inspired by this imaginary experience to try a real expedition to Hart Island… I’d recommend against it.

For one thing, construction will be underway to renovate and shore up the island.

And did I mention it’s extremely illegal? Cell phones, cameras and the press are banned from the island. Getting caught on Hart Island is considered trespassing on prison property, and carries a sentence of 2 years in prison.

Good sources for more information about Hart Island are here:

Melinda Hunt, an artist who started photographing the toppled grave markers in the early 1990s, started amassing a database that is considered more complete than official records, made through a Freedom of Information Act request. She has also published a book called Hart Island and produced a film called Hart Island: An American Cemetery; these and the database all can be found at the Hart Island Project website.

A recent (but pre-Covid) NYT article:

Fishermen at dawn