By Johna Till Johnson

Photo credit: Vlad and Johna in drysuits by Larson Harley, NYC Photographer

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth of sun-split clouds — and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of — wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence.

Hov’ring there, I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air….

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue —

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace.

Where never lark, or even eagle flew —

And, while with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space –

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

John Gillespie Magee, Jr., RCAF (1941)

Vladimir Brezina slipped the surly bonds of Earth on December 13, 2016 (though I like to think he still checks in from time to time). Although the tumbling mirth on which his eager craft traveled was waves, not clouds, this poem captures his spirit perfectly. Here is a little more about his remarkable life, and the joy with which he lived it:

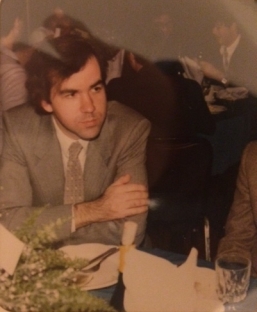

Vladimir Brezina was born on June 1, 1958 in the outskirts of Prague. His father, also Vladimir Brezina, was a civil engineer who designed several notable bridges. His mother, Vlasta Brezinova, was a psychiatrist and moved in artistic circles; Vlad had memories of family friends who were well-known artists and writers. (Both parents are now deceased.)

The family lived in a house (which is still standing) near some woods and a pond, on which he skated in winter. Vlad’s memories of the time were idyllic. He even enjoyed getting punished for his mischief: Apparently his parents would send him to the bathroom for a short “time out”. But the bathroom had a wonderful view and was the warmest room in the house, so it was no hardship—particularly in winter.

Vlad, who was an only child, was close to his extended family. But his comfortable childhood in Prague came to an end when he was 11 years old, when his father took the family on a “vacation” from Czechoslovakia following the Soviet invasion in 1968. Travel into and out of the Soviet-controlled country was becoming difficult, and the time had come for the family to seek its fortunes elsewhere.

Young Vlad waved goodbye to his grandmother as they drove off. He never saw her or his country again.

The family drove through Italy and onward to Libya, where they arrived on August 31, 1969. His father was slated to start a design project, presumably on Monday September 2.

However, on Sunday, September 1, Muammar Gaddafi seized control of the country in a coup d’etat. “Our timing was perfect,” Vlad observed with his characteristic wry humor.

It’s not clear how long the family remained in Libya following the coup, but over the next few years, Vlad lived in Libya and Iraq while his father worked on various projects. The family ultimately settled in the United Kingdom, where they became British citizens, as the Soviets had revoked their citizenship upon departure from Czechoslovakia.

Vlad attended Clifton College, a prestigious boy’s boarding school. At Clifton, Vlad excelled in athletics (he was a rugby player), science, and art. He often told the story of how he re-invigorated the school’s art competition, which his house subsequently won for several years in a row (under his direction), earning him the nickname The Art Fuhrer. Upon graduating from Clifton, Vlad attended Cambridge University (as it was then known) for a year, where he studied art history. He then spent a year at the University of Heidelberg in Germany.

At some point in that period he held a job picking vegetables for scientific research. He recalled with glee that after the experiments were complete, “You could roast [the experimental subjects] and eat them!” Although the experience piqued his interest in science, he found himself growing tired of the long winters in the UK and Northern Europe.

Enticed partly by the prospect of year-round sunshine, and also by his then-girlfriend, he moved to the United States and enrolled in the University of California San Diego, majoring in biology. He became a US permanent resident in 1983, and adopted America as his home. He ultimately obtained his PhD in Neuroscience from UCLA in 1988, with a focus on understanding how small peptides controlled electrical activity in the neurons of the largish marine sea hare, Aplysia californica, which he harvested with great delight from the tidal waters off Los Angeles. His graduate work would set the stage for what became a lifelong effort to understanding how patterns of electrical signaling in complex neurobiological networks controlled behavior.

Vlad had always intended to settle in New York, which he maintained was the only American city with the right combination of energy and chaos. It had captured his imagination early on, and in short order, the newly minted Dr. Brezina became a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University in New York where he quickly became a card-carrying member of the Aplysia behavioral neurobiology community. In 1990, he joined forces with Klaude Weisz at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, where he rose to the level of associate professor. He remained on the faculty at Mt. Sinai until his death in 2016.

Vlad’s scientific work was both theoretically groundbreaking and experimentally elegant. His area of research was in neuromodulation, which is the way nerves communicate with themselves and with muscles in a constantly changing dynamic process. During his years at Mt. Sinai, he introduced an important new theoretical and experimental concept, that of the neuromuscular transform, which he defined as a sort of ‘filter’ that describes how the activity of motor neurons is converted into a muscle contraction. His critical insight, perhaps deriving initially from his studies on complex mathematical transforms, was that this filter is itself dynamic and nonlinear, rather than static (as some had supposed). Moreover, he demonstrated that this dynamism played an important role in animal learning and behavior, enabling the creature to adapt to an uncertain and ever-changing environment.

Throughout his life, Vlad maintained an avid interest in long-distance, human-powered travel. When he lived in the U.K, he hiked a 100 km trail in the Lake District. The summer he was 16, he made a solo journey by bicycle through France, camping at night by the side of the road for several weeks. During his years in California he was a passionate long-distance hiker.

And in New York, in the 1990s, he discovered kayaking.

His first boat was a red Feathercraft K-Light that packed into a backpack weighing a mere 40 pounds. He continued the tradition of red Feathercrafts, getting increasingly larger models that he could pack up and carry on trains and taxis to pursue his adventures. (Sadly, but somehow fittingly, Feathercraft went out of business in December 2016—something Vlad fortunately never knew.)

Vlad quickly became legendary for his knowledge of the New York waterways, and for his feats of endurance in navigating them and others, including New England and later Florida. He discovered many of the now-iconic locations of New York City paddling, including the Yellow Submarine in Brooklyn, the seals on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands, and Alice Austen House and the Graveyard of Ships on Staten Island. (It’s impossible to say who was first to see these from a kayak, but Vlad was among the earliest.)

On his excursions, Vlad simply never seemed to get tired. He once completed a combined circumnavigation of Staten Island and Manhattan without leaving his boat for eighteen hours. His explanation for doing so? “I finished the Staten Island circumnavigation and wanted to keep going— and the currents were right for a Manhattan circumnavigation.” He also wrote about a kayak-sailing adventure during which he and a friend covered 100 nautical miles in 22 hours—again without leaving the boat.

One of his favorite trips was a 10-hour journey around the Elizabeth Islands in April 2002, during which he saw a whale. Subsequent adventures included circumnavigating Long Island in nine days in 2012, and the culmination of a long-time dream: Completing the 300-mile Everglades Challenge, a race from Tampa to Key Largo in Florida, in just under eight days in 2014. Fittingly, his “tribe name”—a nickname adopted by each participant in the Everglades Challenge—was Sea Hare, hearkening back to the creature on which he’d focused the majority of his research efforts. Many of his kayaking adventures are chronicled in our blog Wind Against Current.

Vlad also loved contributing his kayaking skills to others’ adventures. He was a longtime supporter of NYCSwim, a group that organized long-distance swims. Vlad served as “kayak support” for many world-class swimmers, several of whom he accompanied on record-setting feats.

Vlad maintained a lifelong love of poetry (with a particular fondness for Yeats and Philip Larkin), and enjoyed and appreciated opera. He also maintained an avid interest in photography all his life. His earliest photos, dating back to when he was a young teenager in the 1970s, demonstrated emotional depth and an elegant sense of detail—traits that characterized his photos in later life. Over several decades he documented his beloved city, New York, as well as his kayaking trips, with unforgettably vivid images.

Among his blog followers was a group of several dozen photographers, many professionals, who admired his work. Vlad sold a few photographs as book covers and illustrations, but never had any interest in pursuing photography professionally—for him, the work was its own reward.

That attitude was the essence of Vlad, whether in art or science. He often said his defining characteristic was his esthetic sense. Whether paddling, making (or appreciating) art, or conducting science, he always strove always to uncover the eternal and the true. In many respects he lived by Keats’ line “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”

In addition to his esthetic sense, another defining characteristic was his insatiable intellectual curiosity and love of constructive debate.

I first met Vlad in 2009, when we began paddling together. One of our earliest conversations was about the happiness of ducks.

We were paddling a Manhattan circumnavigation in winter, and I’d noticed ducks swimming energetically—and to all appearances cheerfully—in between the blocks of floating ice in the river. “Why are ducks so happy swimming in ice water?” I asked him.

“How do you know they’re happy?” he countered, and we were off on a wide-ranging discussion that included the subjective/objective problem in neuroscience (how can a brain think objectively about itself?), the biology of ducks (apparently they have an entirely separate circulatory system for their legs and feet), and “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” the seminal paper by New York University philosophy professor Thomas Nagel, with which we were both familiar. That conversation lasted the entire six hours of the circumnavigation and continued between us, in various forms, until shortly before his death.

Wedding day, Oct. 17, 2015

I was far from the only one with whom he had such conversations. His former student and subsequent collaborator, Miguel Fribourg, remembers, “The conversation would start discussing a mathematical method, and end up talking about ethics, physics, or Spanish politics.”

Vlad also was deeply, profoundly, and generously, kind. His students remember his love of teaching, a love that came not from ego, but because he was delighted to share ideas with someone. “I will be forever grateful for his generosity and patience in teaching me how to reason, and interpret facts. I also take as a lifelong lesson from him, how to be humble in science and life in general,” says Miguel. Vlad also extended that generosity to the younger generation; for many years, he enjoyed judging science projects for the WAC Invitational Science Fair, at which dozens of Long Island high schools competed.

Vlad had the wonderful talent—which he awakened in me, and many others who were close to him—of appreciating the moment, regardless of what it held. There were of course life’s joyous moments: a breathtaking sunset or star-spangled summer sky; the sound of inspiring music at the opera; and convivial meals with wine, friends, and good food. And when he and I cooked at home, we’d put on music, dance while cooking, and use the fine china and crystal for everyday celebrations.

But Vlad’s genius was not only enjoying these happy moments, but also ones that could have been less than happy. Wind, cold, and rain never fazed him; nor did sweltering nights or water-laden sleeping bags.

I recall once finding ourselves in the dead of night, in below-freezing temperatures, in the custody of puzzled NYPD officers, trying to explain why we and our kayaks were on a beach under the Verrazano Narrows bridge. We quite possibly could have had our kayaks confiscated, and might even have ended up in Rikers Island prison. Instead of being afraid, I realized I was having fun!

There was also the moment, some months after his cancer diagnosis, when we returned home from a particularly harrowing stint in the emergency room. We’d been in the hospital for nearly 40 hours, and as we opened the door to come home, Vlad exclaimed, “Well, that was fun!” And not only did he truly mean it—he was right. It had been fun.

Finally, it’s impossible to write about Vlad without mentioning his ineffably light, witty, gentle sense of humor that often manifested in his characteristic squeaky laugh. His humor relied on clever turns of phrase and occasional goofiness—it was never at the expense of another person. (He loved to mimic expressions and gestures that struck him as entertaining).

I was privileged to be first his paddling partner, then his life partner, and finally his wife (we were married on October 17, 2015). His legacy to me, and to all who knew him, was showing by example how to live in selfless pursuit of truth, beauty, and love—and to enjoy every moment of that life with zest and humor. It will never be the same without him, but what he gave to the world will live on.