By Johna Till Johnson

Medicine, the ministry, and the military. Those were the “three Ms” that—according to my mother—defined the callings of our family, dating back to before the American Revolution. Each is characterized by a commitment to a greater good than self, or even family: Healing, God, country.

That sense of commitment is likely one reason my mother came to marry my father, a naval officer, and it permeated my life growing up.

When we uprooted ourselves to move across the country or around the world for the fifth (or the seventeenth) time, it wasn’t for personal gain. It was because the Navy needed us there to protect our country. That’s what my parents said, and that’s what we believed. When our country called, we came—particularly my father, who spent years underwater in a nuclear submarine.

Some day I’ll write about my father. But meantime, this is enough to explain how I came to spend a recent Friday in Annapolis, at the Naval Academy cemetery, where the ashes of my father’s former commanding officer, Vice Admiral Patrick J. Hannifin, were laid to rest.

It was an uncharacteristically gray, cold, and drizzly day in late spring. I’d gotten up at 3:30 AM to make the four-hour drive to Annapolis. I arrived an hour and a half early, giving me plenty of time to think, and to remember.

As I sat in the white marble open-air “columbarium” overlooking the gray-green water of College Creek, the memories came flooding back. I’d spent three years living on the Naval Academy grounds from ages 8 to 11, while my father was head of the division of Math and Science.

Like many children, I was oblivious to the weight of history. To me, the Academy was a delightful, safe, and well-tended park. I never thought about the fact that the green torpedoes I loved to play on (just the size for an 8-year-old to ride!) were taken from Japan during World War II. Or that I practiced gymnastics, fencing, and swimming in MacDonough Hall (named after a remote ancestor on my mother’s side, Admiral Thomas MacDonough). Though from time to time I passed by Nimitz Library, the Halsey Field House, and the King Hall dining facility, these were all just names to me.

Even this May, as I looked out at the flowing water and the campus beyond, I didn’t think about history. I thought about my father, who died in 2008. I thought about Admiral Hannifin. I thought about all the men I’d known who shared my father’s commitment—and what they had exemplified as leaders, and as human beings.

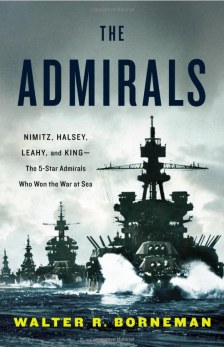

Maybe that’s why, walking through an airport on a business trip a few days later, I was inspired to pick up a book called “The Admirals”, by Walter R. Borneman.

Maybe that’s why, walking through an airport on a business trip a few days later, I was inspired to pick up a book called “The Admirals”, by Walter R. Borneman.

It’s subtitled, “The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea”, which pretty much says it all. It’s about Admirals Nimitz, Halsey, King, and Leahy, each of whom played critical roles in World War II (and who were the only admirals to earn five stars in all of American history).

The book is fantastic. It’s about more than just the people, or the events. It’s about leadership. And it’s about character, and how a flawed individual can rise to greatness—not in spite of, but often even precisely because of, those flaws.

Of the four men profiled by Borneman, three really resonated with me: Nimitz, Halsey, and King.

Nimitz was even-tempered and genial, a consummate engineer who threw himself into every project that was handed to him, and whose supreme satisfaction was a job well done. Halsey was a pugnacious fighter, wisecracking and hotheaded, whose passion was winning the game (or battle). And King was a brilliant careerist, convinced (usually correctly) that he was smarter than anyone else, and determined to win the accolades to which he felt entitled.

Their individual responses to learning of the war’s end sum each up perfectly. In each case, an aide burst into the Admiral’s office with the news that the goal of four years’ uncompromising and exhausting effort had been achieved: the Japanese had surrendered unconditionally.

Halsey’s response was to leap to his feet and begin pounding the aide’s shoulders in joy.

King reportedly looked stricken, and said, “But what am I going to do now?”

And Nimitz? He said nothing, just allowed himself a small, perfectly satisfied smile.

In three following posts, I will post a short sketch of each of these unique leaders, drawn largely from Borneman’s book (which again, I highly recommend) with some additional research:

Halsey: The Unstoppable

Nimitz: The Unflappable

King: The Impossible