By Vladimir Brezina

Gone…

… but not forgotten.

But memories are not enough—the new Tower has risen!

A contribution to this week’s Photo Challenge, Gone, But Not Forgotten.

By Vladimir Brezina

Gone…

… but not forgotten.

But memories are not enough—the new Tower has risen!

A contribution to this week’s Photo Challenge, Gone, But Not Forgotten.

By Johna Till Johnson

Photos by Vladimir Brezina

This is the time of year to stop, take a pause, and think of all the things we’re grateful for. For most of us, that’s family, friends, a warm hearth when it’s cold outside…

And we’re grateful for those, very much so. Particularly our friends, who have held us close recently, and whose warmth and support have reminded us of the very best that human nature can offer.

We’re also grateful for something that’s a bit harder to articulate. It’s the common theme uniting art, poetry, adventure, and the love of nature. It’s that small voice that calls to you: “Pay attention! This thought, or image, or moment, or destination is important!”

Artists know this voice. They live by it. And scientists hear its call, too. As do adventurers. It’s the call that pulls you off the beaten path, onto a new path you didn’t expect to follow, away from all your carefully constructed, sensible plans: We were going to stop and camp here, but… what’s around that next bend? We need to make it to the next waypoint, but… look, there’s a double rainbow! Time to wrap up the experiment, but… what’s going on over here?

You could say it’s the call of the unexpected, or unusual, or unusually beautiful. You could call it, as Vlad sometimes does, an esthetic sense. Or you could just note that sometimes the world, in all its strangeness and beauty, sometimes just reaches out to tap you on the shoulder and say, “Hey! Slow down! There’s something here to appreciate!”

Whatever it is, we’re grateful for that voice, and for the ability to hear it.

We were recently reminded of it in an essay about an American artist, Clayton Lewis, who was also a woodworker and sculptor, and who, by all accounts, lived by this call. Writer and adventurer Willis Eschenbach, who knew him personally, encapsulates that worldview like this:

“Clayton was an artist, and a jeweler, and a boatbuilder, and a fisherman, and a crusty old bugger. He owned three boats, all of them with beautiful lines. I was going to buy a boat once, because it was cheap, even though it was ugly. ‘Don’t buy it,’ he warned, ‘owning an ugly boat is bad for a man’s spirit.’ ” —Willis Eschenbach, November 2014

You can read more about Clayton Lewis, and see photos of his work, including the beautiful seaside studio he constructed, at his website. (One interesting note: He’s one of the very few artists whose bed is now in a museum!)

That voice often calls to Vlad in his photography. Here are a few examples—

(click on any photo to start slideshow)

Tagged Abstract, Art, Artists, Clayton Lewis, Esthetic, Natural Shapes, Photography, Thanksgiving

By Vladimir Brezina

It’s not even winter yet—even though in the US Northeast it feels otherwise—but our thoughts are already turning toward the colors of the coming summer—

All photos from one of the most colorful events of the summer, the Coney Island Mermaid Parade.

A contribution to Ailsa’s travel-themed photo challenge, Colourful.

Posted in Art, New York City, Photography

Tagged Brooklyn, Colorful, Colourful, Coney Island, Mermaid Parade, New York City, Parade, Photography, postaweek, postaweek2014, Travel, Weekly Photo Challenge

By Vladimir Brezina

New York City’s architecture is full of angles—

— along with some curves, of course!

A contribution to this week’s Photo Challenge, Angular.

Posted in Architecture, New York City, Photography

Tagged Angular, Architecture, Manhattan, New York City, Photography, postaweek, postaweek2014, Weekly Photo Challenge

By Johna Till Johnson

Photos by Vladimir Brezina and Johna Till Johnson

It’s hard to believe the Hell Gate Bridge is almost 100 years old.

98, to be exact: The bridge first opened on September 30, 1916. I’ve written about my love for the Hell Gate three years ago, in my birthday greetings to the Bayonne Bridge.

But it’s worth summarizing again why I feel so strongly about the Hell Gate. As I wrote then:

I love bridges. I’m not entirely sure why. Partly it’s the look of them: They seem almost alive, taking off in a leap of concrete, stone, or steel, somehow infinitely optimistic and everlastingly hopeful. Partly it’s their function: Bringing things together, connecting people and places that were previously divided. And of course, bridges often cross moving water—another of my favorite things.

But though I love them all, some bridges in particular hold a special place in my heart.

Many years ago I worked north of New York City (in Connecticut and later in White Plains). The hours were grueling—some days I’d leave my apartment at 5 AM and not return until 11 PM. Sometimes I drove, but I preferred to take the Metro-North train. I relished the peacefulness of the scenery rolling by.

As we crossed the Harlem River, I’d catch sight of one bridge in particular, a study in contrasts: graceful, soaring, yet solid, composed of two steel arches with slightly different curvatures, so they were closer together at the top of the arch and wider apart at the bases, anchored in solid stone towers.

The rising sun would touch this bridge and (so I thought) paint it a lovely shade of rosy pink. The memory of that beauty was often the nicest part of my day.

But for years, I didn’t know what the bridge was called, or even where, exactly, it was. All I knew was that the sight of it reliably brightened my mornings.

One day I happened to mention the bridge to my father, a retired naval officer who had once been stationed in New York City, but now lived hundreds of miles away.

He recognized it immediately from my description: “That’s Hell Gate Bridge,” he said. An odd name for a structure of such harmonious beauty! I hadn’t heard of Hell Gate before, and my dad explained it was where the Harlem River joined the East River. Hell Gate was a treacherous body of water characterized by converging currents and occasional whirlpools that had been the doom of hundreds of ships over the past several centuries.

“As a young ensign, I was on a ship that went through Hell Gate,” my father said. “But I don’t recall that the bridge was pink.” That would have been in the late 1940s; I can’t recall for certain what kind of ship he told me it was, but my memory insists it was a destroyer.

Many years later, I’ll not forget the thrill I had the first time I passed under the bridge, in a far different vessel: My trusty yellow kayak, Photon.

As for the bridge’s color, I later learned my dad was right. The bridge was painted “pink” (actually a color called Hell Gate Red) only in 1996—but the paint has faded to a pastel rose, as you can see.

When doing further research, I learned that:

I also learned that the Hell Gate Bridge was so perfectly engineered that when the main span was lifted into place, the adjustment required was a mere half-inch!

Happy birthday, you beautiful creature. You haven’t aged a bit!

Posted in Architecture, History, Life, New York City, Science and Technology

Tagged Hell Gate, Hell Gate Bridge, New York City

By Johna Till Johnson

I don’t normally pay a lot of attention to the MacArthur Genius awards. The name alone annoys me, because it’s simultaneously elitist and undefined. What makes artist X a “genius” while her peers are merely “talented”? And how can we be sure that out of all the talented people in the universe, the committee has miraculously selected the 12, or 20, that are talented enough to be considered geniuses?

But I do like the notion of awarding creative people a big chunk of change—this year, it was $625,000 over a period of five years—with no constraints. And I also think it’s cool that the awards are so broad-ranging. They go to poets, activists, artists, musicians… and even the occasional scientist, mathematician, or engineer.

Which brings me to this year’s awards. I was overjoyed to see the award given to two people in particular. One was Craig Gentry, a cryptography researcher at IBM’s T. J. Watson research center, who’s done groundbreaking work in the area of homomorphic encryption.

Homomorphic encryption is, in some respects, the holy grail of encryption, because it enables machines to process encrypted data without ever decrypting it. That doesn’t sound like much, but consider: Today, if your email is stored on Google’s servers, it’s fully accessible to Google (which has been known to turn it over to the NSA).

It’s fully accessible because you need Google to do useful things for you (like sort the mail into folders). With homomorphic encryption, you could keep your mail entirely encrypted without giving up any of the functionality (such as folder-sorting). But Google would have no idea what you named your folders, or what was in your email—and the NSA couldn’t read it, either.

Now imagine that instead of ordinary email, we’re talking about medical or financial records—and you can see the benefit.

The issue at the moment is that the computational horsepower required to make homomorphic encryption is immense, so only starting to become practical in real-world applications. But Craig was among the first to show it was theoretically possible. And he did it incredibly elegantly, using a Zeno’s-paradox-like approach that started with “somewhat homomorphic” encryption that iteratively refined itself to become “fully homomorphic”.

And there’s one other thing I like about Craig: He writes really, really well. His Stanford University PhD thesis, which you can find here, is a joy to read. I don’t mind ploughing through dense scientific papers—but I really appreciate it when someone writes gracefully and well.

Another one of this year’s “geniuses” is Yitang Zhang, who is a number theorist at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. Yitang (who I’ve read goes by “Tom”) recently proved the “bounded gaps” conjecture about prime numbers.

Slate’s Jordan Ellenberg (who’s a mathematics professor at the University of Wisconsin) does a much better job explaining what this is and why it matters than I could do. I urge you to read his writeup here.

Suffice it to say that Tom cracked a really, really hard problem in one of the most demanding areas of mathematics. And he’s apparently a really nice, funny, down-to-earth guy, as described in this University of New Hampshire Magazine article.

But that’s not all: Tom is 57—and has done much of his most creative work in the past 10 years (ie from his late 40s onwards).

Mathematics is a field as notorious as gymnastics or ballet for having a youthful peak–the joke among mathematicians is that anyone over 30 is washed up. Gauss, one of the most famous mathematicians ever, did his most significant work by the age of 22—a fact pointed out by my overly gleeful number theory professor when I was 21 or so.

So it’s great to see someone not only doing great things, but doing them at the relatively “advanced” age of 57.

I’m sure the other 19 MacArthur Fellows have done equally great work in their fields. But seeing the awards go to these two made me happy—and I wanted to share my joy with you!

By Vladimir Brezina

As we paddle along the Hudson River  past the piers on Manhattan’s West Side, we pass there, on Pier 66, a large water wheel. Sometimes it is slowly turning as its blades dip into the tidal current that is streaming past. It is a work of art.

past the piers on Manhattan’s West Side, we pass there, on Pier 66, a large water wheel. Sometimes it is slowly turning as its blades dip into the tidal current that is streaming past. It is a work of art.

It is in fact Long Time, by Paul Ramirez Jonas. The concept is simple: The wheel is connected to an odometer that counts the wheel’s rotations. But the piece has large ambitions. The artist is quoted as saying he wanted to create a piece to represent human existence. “It was created with the improbable goal of marking the duration of our lives, species, civilizations and even the planet… [but] its more immediate intent is to place human existence within a geologic time frame… The wheel will rotate indefinitely until it breaks down, or the river changes course, or the seas rise, or other unpredictable circumstances stop it.”

And those unpredictable circumstances have already occurred. After only 67,293 rotations since the wheel was installed in 2007, in 2011 the floodwaters of Hurricane Sandy stopped the odometer. Repairs are not high on the priority list.

However, the wheel itself “is pretty darn sturdy. It was actually happy during Sandy, because it likes the deeper water. You should’ve seen it spinning.”

* * * * *

The Long Time wheel had to be made sturdy enough to resist, among other things, the impact of trash floating in the water. So why not go a step further, and use the rotation of the wheel to pick up the trash?

Last weekend, we visited Baltimore, Maryland. And, walking around the Inner Harbor, we spied from a distance a familiar shape—a water wheel. At first we thought that, like Long Time, it was an artwork of some kind. But when we came closer, we realized that it was something more practical.

This water wheel is a trash collector.

It’s mounted on a floating platform moored at the point where Jones Falls, a river that drains quite a large watershed to the north of the city—and brings down a corresponding amount of floating trash—empties out into the Inner Harbor. The river current drives the water wheel. (There is also solar power for days when the river current is too weak.) The wheel in turn drives a series of rakes and a conveyor belt. The rakes rake the trash, already concentrated by floating booms, up onto the conveyor belt, which deposits the trash into a floating dumpster. Simple!

And yes, it is also a work of art.

More detailed photos of the trash collector are here, and here is a video of it in operation:

The trash collector can collect up to 50,000 lbs of trash per day. By all accounts, although it hasn’t been operating long yet, it’s already made a very promising contribution toward solving Baltimore Harbor’s trash problem. It’s been much more effective, at any rate, than the old way of picking up the floating trash with nets from small boats. “After a rainstorm, we could get a lot of trash in Baltimore Harbor. Sometimes the trash was so bad it looked like you could walk across the harbor on nothing but trash.” Last weekend, as we walked around it, the harbor looked remarkably clean.

Much cleaner, in fact, that some parts of New York Harbor. And we can think of a number of rivers draining into New York Harbor where such a trash collector could be ideally positioned.

Take the Bronx River, for instance. It already has a floating boom to hold back the huge amount of trash that floats down the river—trash that must be periodically removed. A water wheel would do the job effortlessly.

Take the Bronx River, for instance. It already has a floating boom to hold back the huge amount of trash that floats down the river—trash that must be periodically removed. A water wheel would do the job effortlessly.

So, let’s hope there are more water wheels, not merely decorative but also practical, in New York’s future!

________________________________________________________

More details about Baltimore’s water wheel can be found here:

Posted in Art, New York City, Science and Technology

Tagged Baltimore, Marine Art, New York City, New York Harbor, Trash, Water Wheel

By Johna Till Johnson

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

There are no extraordinary men, just extraordinary circumstances that ordinary men are forced to deal with.

—Admiral William (“Bull”) Frederick Halsey, Jr.

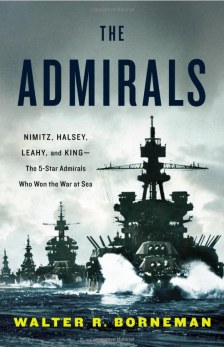

This sketch is one of several inspired by the book, The Admirals: The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea, by Walter R. Borneman. It’s about Admirals Halsey, Nimitz, King, and Leahy, each of whom played critical roles in World War II, and were the only admirals to earn five stars in all of American history. (For the other sketches in the series, see Triptych: Three Admirals.)

More than that, the book is about leadership, character, and how a flawed individual can rise to greatness—not in spite of, but often even precisely because of, those flaws.

Halsey was a pugnacious fighter, wisecracking and hotheaded, whose passion was winning the game (or battle). His courage and determination helped re-energize and inspire a Navy demoralized and depleted by the hideous surprise of Pearl Harbor. Yet his appetite for the fight paradoxically cost him participation in some of the defining battles of the Pacific, and could have cost the war. But anything he did, he did wholeheartedly—and there was never any question of stopping him.

By Johna Till Johnson

Medicine, the ministry, and the military. Those were the “three Ms” that—according to my mother—defined the callings of our family, dating back to before the American Revolution. Each is characterized by a commitment to a greater good than self, or even family: Healing, God, country.

That sense of commitment is likely one reason my mother came to marry my father, a naval officer, and it permeated my life growing up.

When we uprooted ourselves to move across the country or around the world for the fifth (or the seventeenth) time, it wasn’t for personal gain. It was because the Navy needed us there to protect our country. That’s what my parents said, and that’s what we believed. When our country called, we came—particularly my father, who spent years underwater in a nuclear submarine.

Some day I’ll write about my father. But meantime, this is enough to explain how I came to spend a recent Friday in Annapolis, at the Naval Academy cemetery, where the ashes of my father’s former commanding officer, Vice Admiral Patrick J. Hannifin, were laid to rest.

It was an uncharacteristically gray, cold, and drizzly day in late spring. I’d gotten up at 3:30 AM to make the four-hour drive to Annapolis. I arrived an hour and a half early, giving me plenty of time to think, and to remember.

As I sat in the white marble open-air “columbarium” overlooking the gray-green water of College Creek, the memories came flooding back. I’d spent three years living on the Naval Academy grounds from ages 8 to 11, while my father was head of the division of Math and Science.

Like many children, I was oblivious to the weight of history. To me, the Academy was a delightful, safe, and well-tended park. I never thought about the fact that the green torpedoes I loved to play on (just the size for an 8-year-old to ride!) were taken from Japan during World War II. Or that I practiced gymnastics, fencing, and swimming in MacDonough Hall (named after a remote ancestor on my mother’s side, Admiral Thomas MacDonough). Though from time to time I passed by Nimitz Library, the Halsey Field House, and the King Hall dining facility, these were all just names to me.

Even this May, as I looked out at the flowing water and the campus beyond, I didn’t think about history. I thought about my father, who died in 2008. I thought about Admiral Hannifin. I thought about all the men I’d known who shared my father’s commitment—and what they had exemplified as leaders, and as human beings.

Maybe that’s why, walking through an airport on a business trip a few days later, I was inspired to pick up a book called “The Admirals”, by Walter R. Borneman.

Maybe that’s why, walking through an airport on a business trip a few days later, I was inspired to pick up a book called “The Admirals”, by Walter R. Borneman.

It’s subtitled, “The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea”, which pretty much says it all. It’s about Admirals Nimitz, Halsey, King, and Leahy, each of whom played critical roles in World War II (and who were the only admirals to earn five stars in all of American history).

The book is fantastic. It’s about more than just the people, or the events. It’s about leadership. And it’s about character, and how a flawed individual can rise to greatness—not in spite of, but often even precisely because of, those flaws.

Of the four men profiled by Borneman, three really resonated with me: Nimitz, Halsey, and King.

Nimitz was even-tempered and genial, a consummate engineer who threw himself into every project that was handed to him, and whose supreme satisfaction was a job well done. Halsey was a pugnacious fighter, wisecracking and hotheaded, whose passion was winning the game (or battle). And King was a brilliant careerist, convinced (usually correctly) that he was smarter than anyone else, and determined to win the accolades to which he felt entitled.

Their individual responses to learning of the war’s end sum each up perfectly. In each case, an aide burst into the Admiral’s office with the news that the goal of four years’ uncompromising and exhausting effort had been achieved: the Japanese had surrendered unconditionally.

Halsey’s response was to leap to his feet and begin pounding the aide’s shoulders in joy.

King reportedly looked stricken, and said, “But what am I going to do now?”

And Nimitz? He said nothing, just allowed himself a small, perfectly satisfied smile.

In three following posts, I will post a short sketch of each of these unique leaders, drawn largely from Borneman’s book (which again, I highly recommend) with some additional research:

Halsey: The Unstoppable

Nimitz: The Unflappable

King: The Impossible